The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act) contains a requirement that the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), author of many of the rules under the act, publish an assessment of its "significant rules and orders" within five years of their effective date. Among the rules that CFPB has determined to fit that category are the Ability-to-Repay/Qualified Mortgage (ATR/QM) Rule and the Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act (RESPA) Mortgage Servicing Rule. Both came into effect in January 2014 and assessment of both were published this week.

What follows is a summary of the assessment of the Ability-to-Repay/Qualified Mortgage (ATR/QM) Rule. A summary of the RESPA Servicing rule will follow at a later date.

The ATR/QM assessment looks at four broad categories; whether the rule is effective in assuring the ability to repay, its impact on access to credit and restricting undesirable loans, creditor cost and the costs of credit, and effects on market structure. It does not include any cost-benefit analysis. It also does not address the necessity of the requirement or alternate ways Congress might have responded to the housing crisis.

The key requirement of the Rule is that lenders make a reasonable and good faith determination that the consumer has a reasonable ability to repay before issuing a mortgage loan and defines certain factors a lender must consider in making that decision. Lenders who do not comply can be liable for damages under the Truth-in-Lending-Act (TILA).

The Rule defines a QM as fully amortizing with a term no greater than 30 years. Except for small loans, the sum of points and fees cannot exceed 3 percent of the loan and a borrower's debt-to-income (DTI) level is capped at 43 percent. The Rule creates a Temporary GSE QM which will expire in January 2021 qualifies as QM most loans eligible for purchase by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac (the GSEs).

A QM loan is presumed to satisfy the ATR requirement, providing a "safe harbor" for the lender. A borrower with a "high cost" loan is given an opportunity to rebut the safe harbor assertion.

Assuring

Ability to Repay

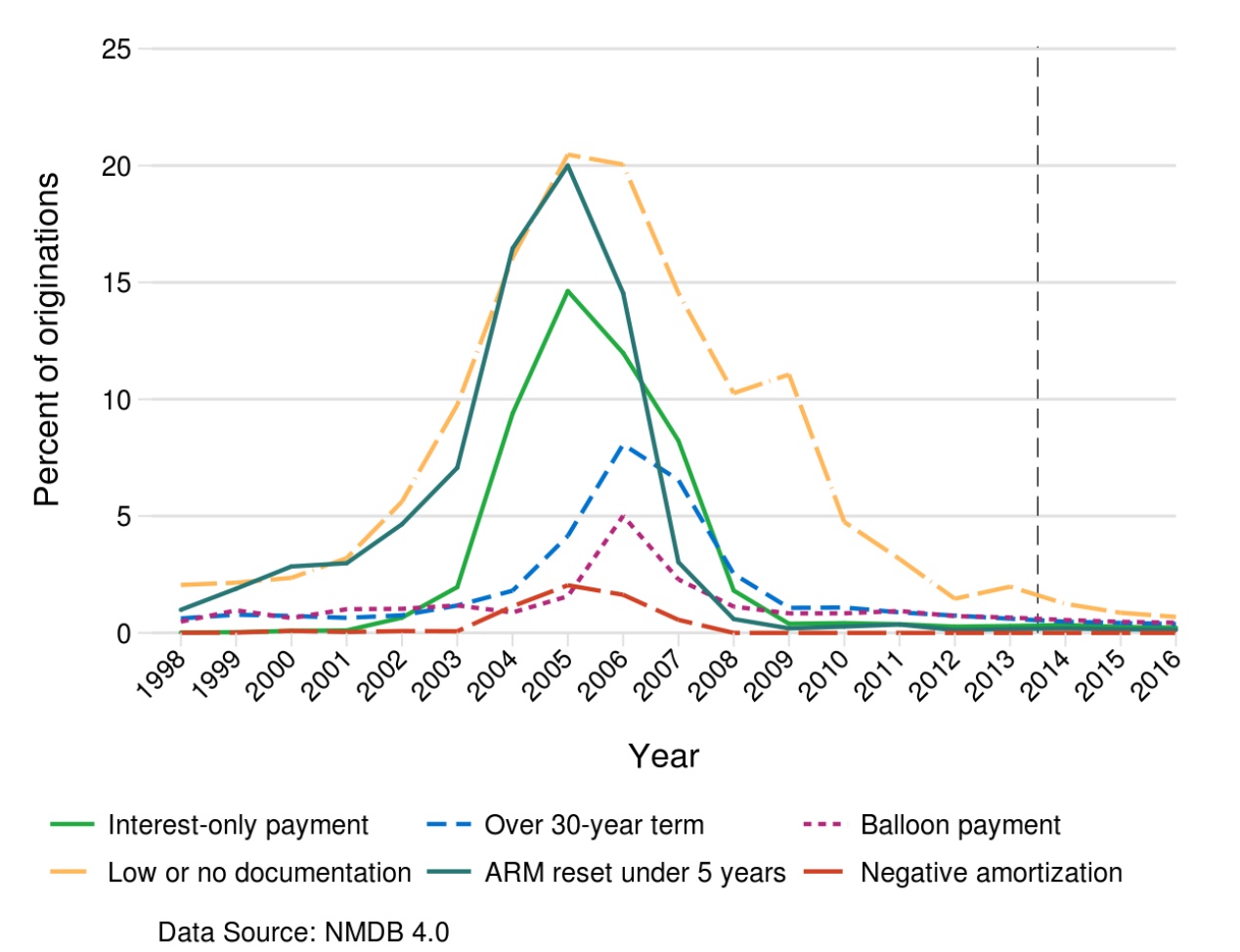

The assessment says that approximately 50 to 60 percent of mortgages originated between 2005 and 2007 which were foreclosed within their first two years had features that the ATR/QM rule restricts; i.e. initial low rates that reset higher or with limited or no documentation. Loans with these features had largely disappeared before the rule was adopted and today appear restricted to a few highly credit-worthy borrowers.

High DTIs are historically associated with higher levels of delinquency. These are now constrained from returning to crisis-era levels by a combination of the ATR requirement and GSE underwriting rules. Currently a DTI limit of 45 percent applies to most loans and only 5 to 8 percent of conventional purchase mortgages exceed that level compared to about one-quarter of loans originated in 2005-2007.

CFPB looked at a sample of loans that become delinquent with two years of origination and found the ATR rule was not generally associated with improvements in performance. This, they say, is due to historically low delinquency rates on loans originated in the tight credit environment immediately preceding the rule. The rate for non-QM loans with DTIs over 43 percent remained steady at 0.6 percent; the rates of GSE loans with DTIs above 43 percent originated in 2012-2013 was 0.6 percent and increased to 1.0 percent for 2014-2015 originations. "Thus, although the performance of non-QM loans did not improve in absolute terms, it has improved relative to the performance of comparable QM loans."

Access

to Credit and Restrictions on Unaffordable Loans

The implementation of the rule did not create a significant break in the volume of mortgage application nor in the approval rate. This is partly attributable to the already-tight credit in effect at the time and in part to the breadth of the QM definition and the safe harbor it afforded. CFPB estimates that 97 to 99 percent of loans originated in the year prior to the Rule (2013) would have satisfied QM requirements.

However, there are market segments where the rule is more likely to have restricted credit:

- Borrowers with high DTIs. CFPB's analysis indicates the Rule displaced between 63 and 70 percent of approved purchase applications among non-QM, high DTI borrowers from 2014 to 2016, a reduction of 1.5 to 2.0 percent of all home purchase loans made by the nine lenders studied. Other studies back up these findings. The was also reduction in credit access for refinancing in 2014 followed by gradual improvements in later years.

CFPR also found that approval rates for high-DTI non-QM borrowers declined across all credit tiers and income groups with the result that the average credit score and income for declined borrowers increased after the Rule took effect. Other industry data indicates that delinquency rates for non-QM high DTI borrowers did not decrease post-rule. Together these findings suggest loss of credit access was driven by lenders trying to avoid the risk of litigation by consumers challenging a violation of the ATR requirement rather than by rejection of borrowers unable to repay the loan.

- Self-Employed Borrowers. Self-employed borrowers who do not qualify for GSE loans (or those with other federal guarantees) generally need to qualify under the General QM standard. Responses to a Lender Survey indicate that lenders may find it difficult to comply with rules related to the documentation and calculation of income and debt. Yet application data indicates that approval rates for non-high DTI, non-GSE eligible self-employed borrowers have decreased by only 2 percentage points under the rule.

- Small Loan Borrowers. The points-and-fees cap on QM loans could impact small

borrowers as these those costs will constitute a higher percentage than for larger loans. Analysis of Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) data indicates that the Rule has had no effect on credit access for such loans. Lenders indicate that exceeding the points and fees cap is sufficient rare that lenders address loans on a case-by-case basis and they are rarely denied.

Creditor Costs and the Cost of Credit

The Rule has requirements for documentation that may differ from pre-Rule practices for some lenders and it creates potential liability for ATR violation. There are also additional capital requirements under a separate rule administered by other agencies which may add to funding costs.

At the aggregate market level, the Rule does not appear to have materially increased costs or prices. The Mortgage Bankers Association's (MBA's) quarterly survey of independent lenders finds origination costs have increased over the last decade but saw no distinct change at the time the Rule was implemented. MBA also found that the spread between average 30-year mortgage rates and the relevant Treasury yield has remained constant post-Rule.

A majority of respondents to CFPB's Lender Survey indicated that their business model has changed as a result of the Rule and of those some pointed to increased documentation or staffing while others said they had chosen not to originate non-QM loans. The nine lender providing data said their lost profits amounted to between $20 million and $26 million per year.

Evidence is mixed as to whether the Rule has increased the price of non-QM loans. None of those nine lenders specifically charge extra for them. A review of rate sheets from 40 lenders found an adjustment for the loans to be very infrequent. Nevertheless, 23 of 204 lenders responding to a survey indicated applying an increase and Federal Reserve research finds loans with high DTIs to be substantially more expensive than those below 43 percent.

Effects

on Market Structure

The current QM category is broad due to the Temporary GSE QM rule. The GSEs, contrary to expectations, have maintained a persistently high share of mortgage lending as the private-label securities market remains small.

CFPB has looked at whether the Temporary GSE QM provision has caused an increased reliance on the GSEs' Automated Underwriting Systems (AUSs) for loans not sold to the GSEs. They found no immediate increase in the aggregate volume of submissions to the AUSs relative to the volume of loans purchased by the GSEs but there does seem a somewhat higher use in recent years, particularly for loans which do not fit requirements or are more difficult to document such as those made to self-employed borrowers.

There are allowances within the Rule for small creditors to originate high-DTI and balloon loans as long as they hold them in portfolio for two years. Approximately 90 percent of depository institutions reporting HMDA data in 2016 met the small creditor definition and accounted for about 24 percent of mortgage loans. The Rule does not appear to be constraining the activities of these lenders.

There are systemic differences between loans made by small creditors and non-small creditors. The former hold a larger share of their loans in portfolio, although there was a notable decline in that share in 2016, coinciding with an expansion of the small creditor definition. Similarly, a larger share of their mortgages is made in rural counties or to finance manufactured homes.

A survey by the Conference of State Banking Supervisors in 2015 found that a larger share of small creditor portfolio loans was non-QM than was true for the larger lender who responded to the survey. Smaller creditors also reported declining a smaller percentage of applications. To the extent small creditors declined applications, they were less likely that their larger counterparts to attribute their denial to the Rule's requirements.

The assessment also looked at whether adoption of the Rule has affected mortgage processing time. After controlling for confounding factors, it found that immediately after adoption closing times increased by about 3-1/2 days for refinance loans, but the estimated effect on purchase loan closing times was much smaller, at a little over one day. The report adds that it can be presumed these were short-term results.