Conventional wisdom, the lending version, holds that refinance loans are inherently less risky than purchase loans, but a recent analysis from the Urban Institute (UI) refutes this contention. In fact, Linda Goodman, Co-director of UI's Housing Finance Policy Center says rampant refinancing probably played a major role in the housing crisis.

Goodman, writing in UI's Urban Wire blog says despite ample evidence that it was risky products rather than lending to riskier borrowers that majorly contributed to the crisis, many continue to blame government policies toward homeownership. However, at the height of the boom it was refinanced loans that were more likely to default. This was largely due to people treating their homes as ATMs through cash out refinances.

Eighty-four percent of refinances through Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (the GSEs) in 2006 and 2007 were cash-out. Their "sloppier underwriting" meant that, for any set of observable risk characteristics, they defaulted more often than purchase mortgage loans.

UI's research looked at 30-year GSE mortgages originated between 1999 and 2015. All loans were "full-document" and amortizing; 56 percent were refinance loans and 44 percent used to purchase a home and none were nontraditional products such as interest-only loans.

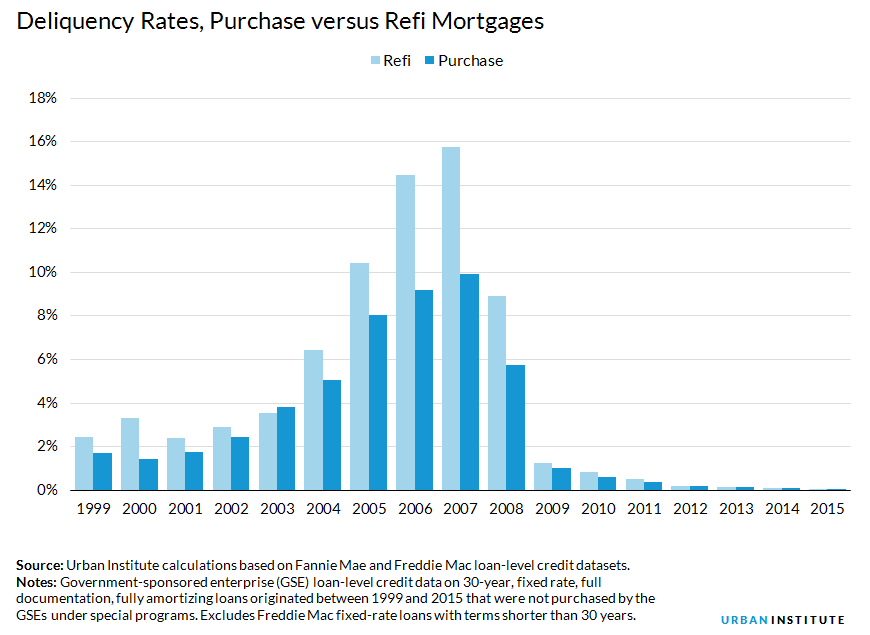

Goodman says over the entire period 4.48 percent of refis and 3.3 percent of purchase loans went, as some point, more than 180 days delinquent. However, in 2007, the respective rates of serious delinquency were 15.78 percent and 9.95 percent. As can be seen in the figure below, delinquency rates since 2009 have been low for all loans; the largest differences in performance between the two loan types were in vintages between 2004 and 2008.

Refinance loans are generally thought to be less risky than purchase loans because the borrowers have a known payment history. Refis also tend to have stronger credit characteristics such as lower loan-to-value (LTV) and debt-to-income (DTI) ratios. During the analysis period, refis had an LTV ratio of 68.4 percent while purchase loans averaged 79.2 percent. Purchase loans had average DTIs of 34.9 percent, marginally higher than the 33.4 of refinances. The higher risks for purchase loans were partially offset by slightly higher FICO scores 730 versus 736 for refinance borrowers.

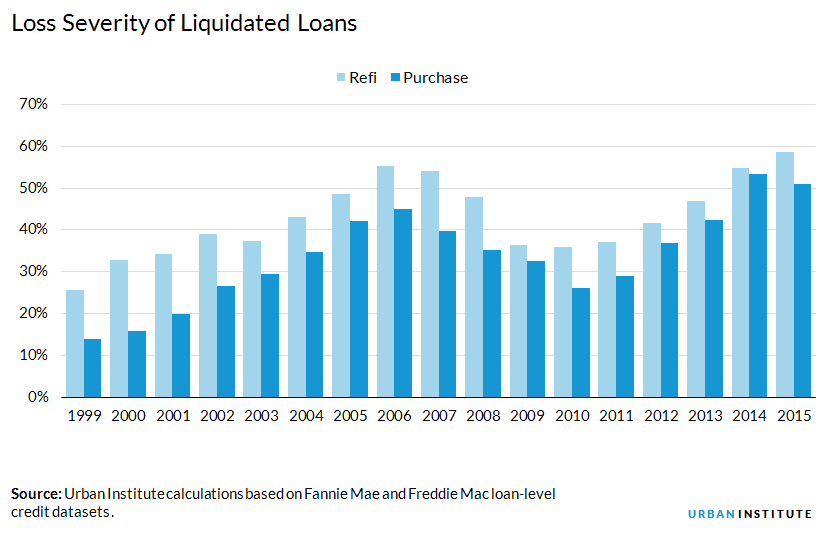

Goodman also looked at the severity of loss to lenders when loans refinances go seriously delinquent verses purchase loans. She found the 25 to 30 percent of loans that become 180 days or more past due or either brought current to paid off. Sixty percent liquidate and 10 to 15 percent linger, neither coming current nor being liquidated, but persistently delinquent. Purchase loans are marginally less likely to become current and are more likely to be liquidated than their refinance counterparts, yet lenders lose more money with a refi that becomes delinquent than a purchase mortgage.

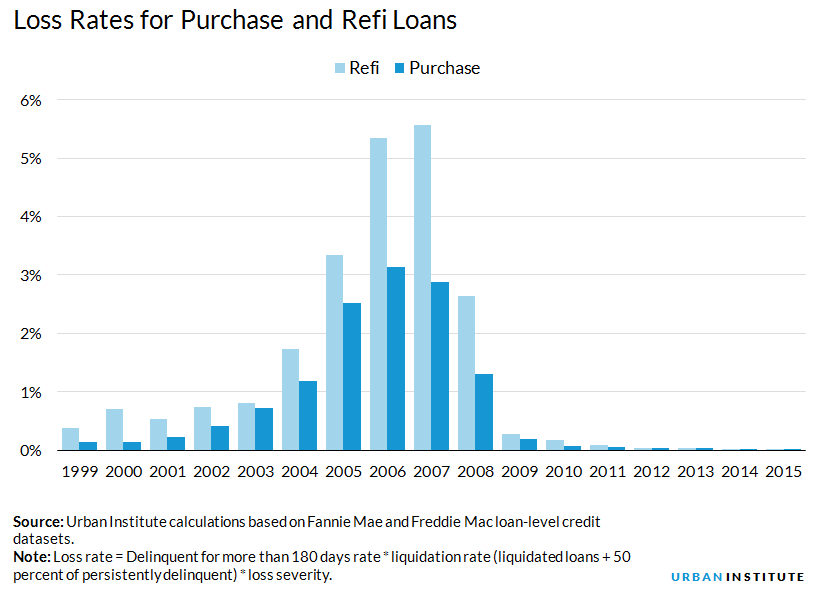

Severity with a purchase loan is about 10 points lower than a refi. This is partly because a lot of loans have mortgage insurance, but even where there is none, purchase loans consistently have lower severities. The figure below shows that the loss rates for refinance mortgages are higher than those for purchase mortgages, with the largest differences between 2005 and 2008.

Goodman concludes that the analysis shows that for the same kind of loan, GSE losses were more common and the losses greater for refinance than for puchase mortgages. "Although there is a lot of blame to go around for the poor quality of loans before the housing crisis, these data reaffirm that purchase borrowers were not the primary culprits."