If you were to review a pile of mortgage applications randomly pulled from all of those submitted what age group do you think would look the best, the most creditworthy on paper?

Trick question? Not at all. CoreLogic Economist Archana Pradhan recapped such a review in the company's Insights blog and the results were just what you would expect. The older the borrower, the stronger the credit profile.

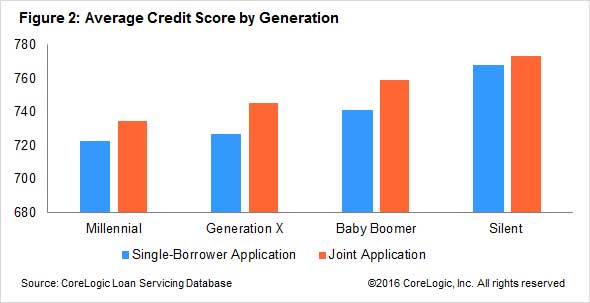

Looking at the application information by age group she found the lowest credit scores belonged to Millennials, those who are 19 to 35 years of age this year. The average score for members of that age group who applied for a mortgage between March and May 2016 was 730 compared to 770 for the Silent Generation (those 71 and older.) In the middle of the progression were Gen Xers, the 36 to 51 year olds, with an average score of 738 and 53 Baby Boomers (age 52 to 70) at 753.

This only makes sense. The younger the household the less time it has had to build a credit history. This can be compounded by limited savings and lower levels of income at the early stages of their careers.

Mitigating the generational differences a bit (especially with Gen X), was a higher average credit score for mortgage applications with two borrowers rather than a single borrower, regardless of generation. Millennials, for example, had an average score of 722 for single-borrower applications against 735 for joint applications.

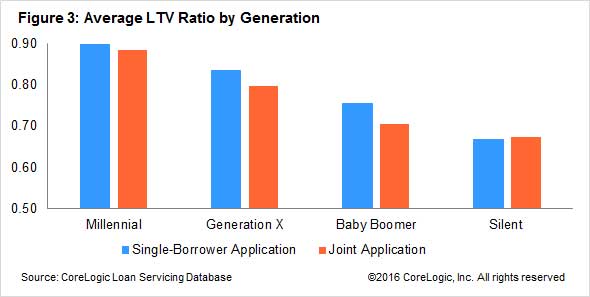

Many of the same factors that affected credit scores, early career income, fewer savings, as well as less time to build equity through homeownership, led to a higher loan-to-value (LTV) ratio among younger borrowers. That number drops with age as steadily as the credit score rose and again with a benefit going to those two-borrower applicants. The average LTV ratio for Millennials in Pradhan's sample was 89 percent compared to 81 percent for Generation Xers, 73 percent for Baby Boomers, and 68 percent for members of the Silent Generation.

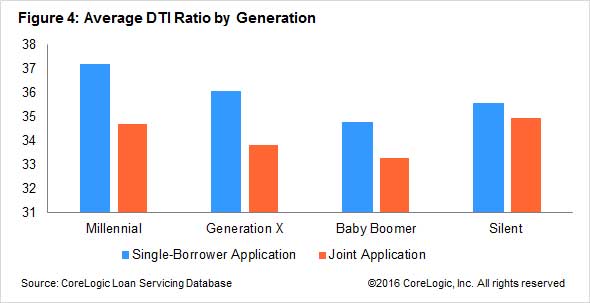

The pattern changes slightly for debt-to-income (DTI) ratios. Millennials, often burdened by student debt, had the highest ratios at 37 percent for single-borrower applications and 35 percent for joint applications. The author doesn't provide hard numbers for the other three generations' ratios but the chart below pretty clearly indicates that it is the number of names on the application (undoubtedly indicating the number of incomes going into the equation) rather than age that is driving the results. Also breaking the pattern is the higher DTI among the oldest cohort, many of whom are probably retired and on a fixed income.

The author concludes, "Workers who are early in their working careers, such as today's Millennials, generally experience more rapid earnings growth than older workers, and more rapid income growth than retired individuals. While their credit-risk attributes may look weaker than for older cohorts, this potential for faster earnings growth and more savings accumulation are important offsets in their risk profile."