Since the start of the housing crisis the experts have noted the tendency young adults to continue to live in their childhood homes. This they say is contributing to the diminished rate of household formation which is, in turn, lowering homeownership rates in the lower age cohorts with the ultimate effect of holding back the housing and construction recoveries.

Even when young adults move out of their parents' basement, as the saying goes, they tend to share housing with other young adults. The economists at CoreLogic have coined the name "the Renter Generation" as an alternative designation for the age group more broadly referred to as Millennials, those born between the early 1980s and early 2000s.

Fannie Mae focused on the issue in a Commentary piece released on Tuesday, using data collected through its National Housing Study (NHS) over the first two quarters of 2014. Adult decision makers were asked questions about their young adult children living at home, so all responses are from the parents' perspective. The analysis addressed answers regarding two age groups, 18 to 22 year olds (younger adult children) and 23-34 year olds (older adult children.)

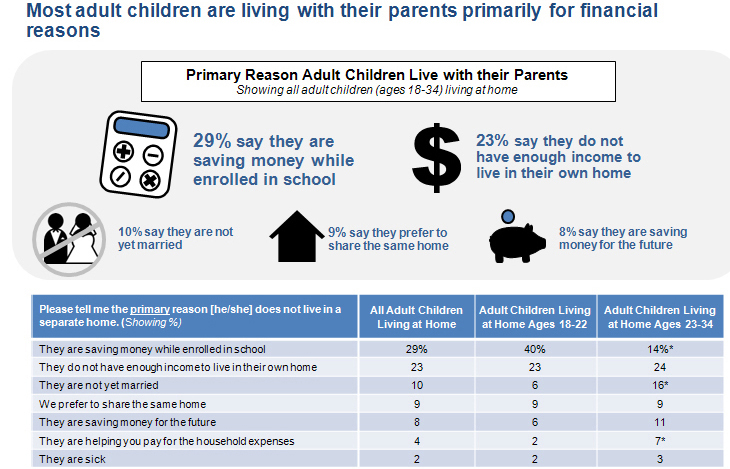

Authors of the Commentary, Why Are Young Adults Living with Their Parents and When Will They Move Out? suggest that the issue of Why is driven by a combination of personal financial constraints, age of the adult child, and parental preferences.

The NHS notes that the percentage of young adults between the ages of 18 and 34 who are living with their parents increased from the 27 percent average that prevailed between 1990 and 2006 to 31 percent in 2013. This means that some 22 million young adults, a group that traditionally provides a substantial share of first-time homebuyers is delaying the decision to form a household. Young adults also have been experiencing higher rates of unemployment and are delaying marriage, other factors surrounding their lack of household formation.

Financial reasons were the primary response given by parents for why their adult children are still living at home. As regards the younger adult children, parents by a large margin say that they are "saving money while enrolled in school." It has also been reported in the survey that the majority of this group are "not currently employed in a paying job" or "employed part-time" which impedes their ability to live on their own.

A wider range of responses was given why older adult children were still at home. Top responses include:

-

"They do not have enough income to live on their own."

-

"They are not yet married."

-

"They are saving money while enrolled in school."

In aggregate the primary reason for the older age group was financial concerns even though half of that group is employed full time.

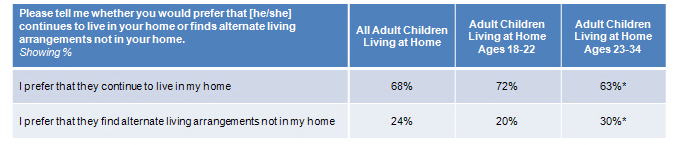

The survey also found that most parents (68 percent) actually prefer having their adult children live with them. As the chart below indicates this preference was significantly lower among the parents of older adult children than among parents of younger adults.

There was also a difference in answers regarding financial attitudes. A higher share of parents of younger adult children said their recent personal financial situation had gotten better (+5 percent) or was expected to get better (+11 percent) than the responses from parents with older adult children. The parents of younger children also were more frequently employed full-time, perhaps partially due to age differences although reported rates of retirement in the two groups were similar.

There were also significant differences in attitudes by adult children age groups in their respective parents' attitudes about the potential for their children to move out on their own. Fifty-two percent of parents with older adult children expect their children to move out in less than 2 years, whereas parents with younger adult children were almost evenly split between less than 2 years (38 percent) and 2 to 5 years (34 percent). Overall the majority of the children expect that they will more likely rent than buy a home when they move out of their parents' house.

Fannie Mae adjusted these findings to be more comparable to the 2012 American Community Survey (ACS) which showed that 67 percent of householders under the age of 34 were renting and the homeownership rate was 33 percent. In the NHS survey 66 percent are more likely to rent, 34 percent to buy. "This could imply that young adults currently living with their parents may not have a substantial impact on shifting the near-term homeownership rate when they do move out of their parent's home," the commentary says. It adds that a recent NHS found that more than 90 percent of young renters said they are likely to buy a home at some point in the future.

As results suggest that the age of the adult child and personal financial constraints combine with parental preferences to keep adult children at home, it remains to be seen whether that latter reason will lead to a lifestyle change that slows household formation even as the economy improves. However since financial reasons account for most parental responses as to why young adults are living at home, it seems likely that they, especially the older group, will start to form their own households once they feel confident about their financial situation and future prospects.

Another commentary, this time by CoreLogic's Chief Economist Mark Fleming in his company's blog, looks at one of the financial constraints alluded to in the Fannie Mae piece. In "Generation Renter's" Student Loan Burden" Fleming looks at the extent to which that debt may be impacting homeownership.

He recounts a discussion by a panel of experts on housing, finance, and education at an Urban Institute event addressing whether this debt is actually preventing the Millennial generation (or Fleming's term "Generation Renter") from becoming homebuyers.

The panel featured Jeffrey P. Thompson, economist at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System; Meta Brown, senior economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York; Sandy Baum, senior fellow at the Urban Institute and research professor of education policy at George Washington University; and Beth Akers, fellow at the Brown Center on Education Policy at the Brookings Institution. Fleming said the evidence seemed to suggest the answer is no.

First, a study by Akers and her Brookings colleagues found that the student debt burden, the required monthly debt payment as a percentage of income, has remained practically unchanged since the mid-1990s. Even with the aggregate debt now above $1 trillion, with more individuals holding greater amounts of debt, and with stagnant U.S. income growth, the facts cannot lead to the conclusion that student loan debt is a bigger burden that will prevent homeownership. If going to college still increases one's earning potential and the debt burden is unchanged from the 1990s and young people then found a way to buy a home, why wouldn't young people today, with the same relative burden, be able to do the same?

Thompson's empirical modeling of the level of educational attainment among those who have student loan debt shows little evidence of a strong reduction in the likelihood of homeownership for those who complete their education, but does find the likelihood reduced those with student debt who do not complete their education. Accumulating the debt but not earning the degree results in the burden without any benefit as, on average, getting a college degree results in higher earnings.

Baum noted that one must be careful with the averages used in the Brookings analysis because of wide variations in the outcomes for those with debt. In particular, the detrimental impact on financial stability for those who don't complete a degree. The post-secondary system and related financing policies need to consider and address the burden of college debt without the benefit of a degree