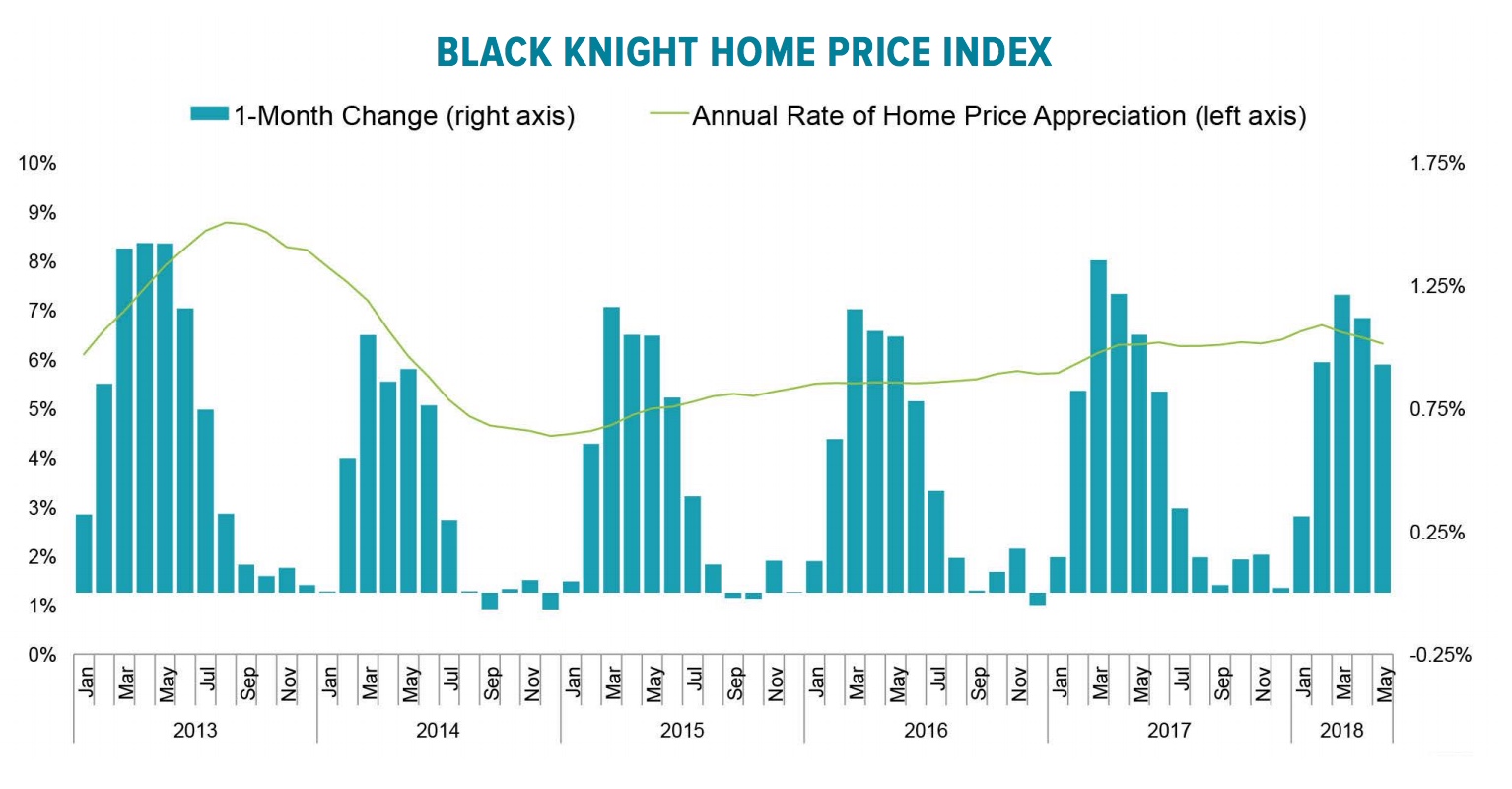

Altough it was forecast to happen long ago, it seems price gains throughout the U.S. are moderating. Black Knight, in its August Mortgage Monitor, claims that is the case. While prices are still rising, the company says its Home Price Index slowed each month from March through May, the first three-month slide in nearly four years. Prices in 32 states and 33 of the 50 largest markets exhibited that same pattern.

Ben Graboske, executive vice president of Black Knight's Data & Analytics division said, "In May - typically one of the strongest months of the year for home price growth - every state in the nation saw home prices increase. However, the average monthly gain in value of less than one percent was the lowest for any May in the last four years. All that said, the annual rate of home price growth is still historically high at 6.3 percent, some 2.5 percentage points above long-term norms. For more than six years, we've been riding a wave of home price appreciation above the 25-year average. The question now is whether tightening affordability will end that streak and if more deceleration is on the horizon."

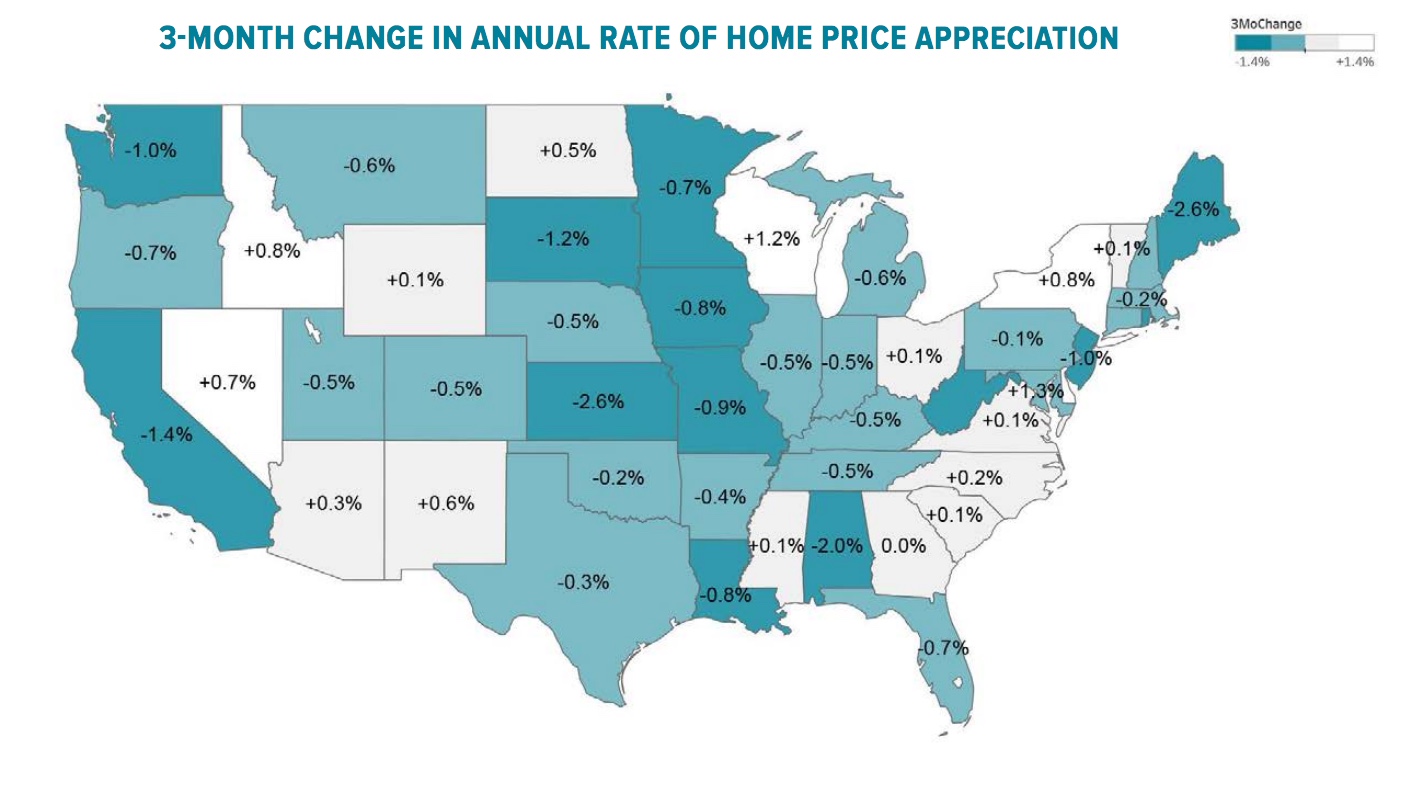

California has exhibited the greatest rate of deceleration, slowing by more than three times the -0.93 percent rate of the nation as a whole. The annual appreciation fell from 10.2 percent in February to 8.8 percent in May. Other states that appear to be experiencing notable cooling are New Jersey, Washington, Oregon, Florida, and Colorado. Many of the states had already exceeded their long-term affordability benchmarks - measures based on median home prices in relation to median income levels. However, Black Knight notes that even some states in the Midwest, which still has relatively affordable housing, are cooling down.

However, if 32 states are decelerating that leaves 18 that are not. These are largely in the West - Idaho, Nevada, New Mexico Arizona, and the South Atlantic states. The highest price growth, an average annual growth of 1.2 percent over the three-month period, was in Michigan.

Among metro areas that are seeing the greatest slowdown are those that have experienced the greatest increases. Seattle, where prices have risen annually by double digits for several years, slowed by 2.33 percent over the three months, followed by Riverside, at 2.13 percent, and three other California cities, San Diego, Los Angeles, and Sacramento where the slowdown ranged from 1.84 down to 1.35 percent. Areas where prices are still accelerating include Las Vegas and Phoenix, two cities that saw among the largest price drops during the housing crisis, and Washington, DC, one of the nation's least affordable metros.

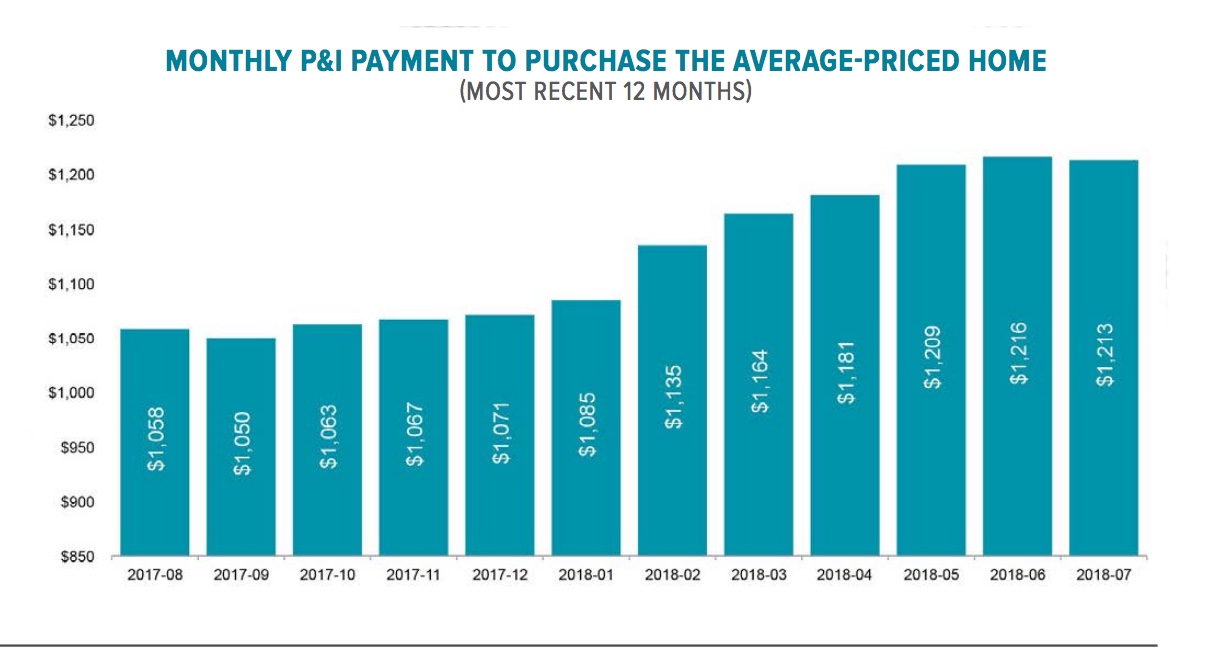

Graboske said the recent cooling of home price gains and slight reprieve in rising interest rates have combined to stabilize affordability in recent months. "As rates have ticked down from 4.66 percent in late May to 4.52 percent in mid-July, the monthly principal and interest payment to purchase the average home has only increased by $4 per month - significantly less compared to the $138-per-month increase we saw over the first five months of 2018. Still, the $1,213 in principal and interest per month needed to buy the average home remains near a post-recession high. While that represents a nearly $500 per month increase from the bottom of the market in 2012, it's important to keep in mind that it's still roughly 13 percent less than was required back in 2006."

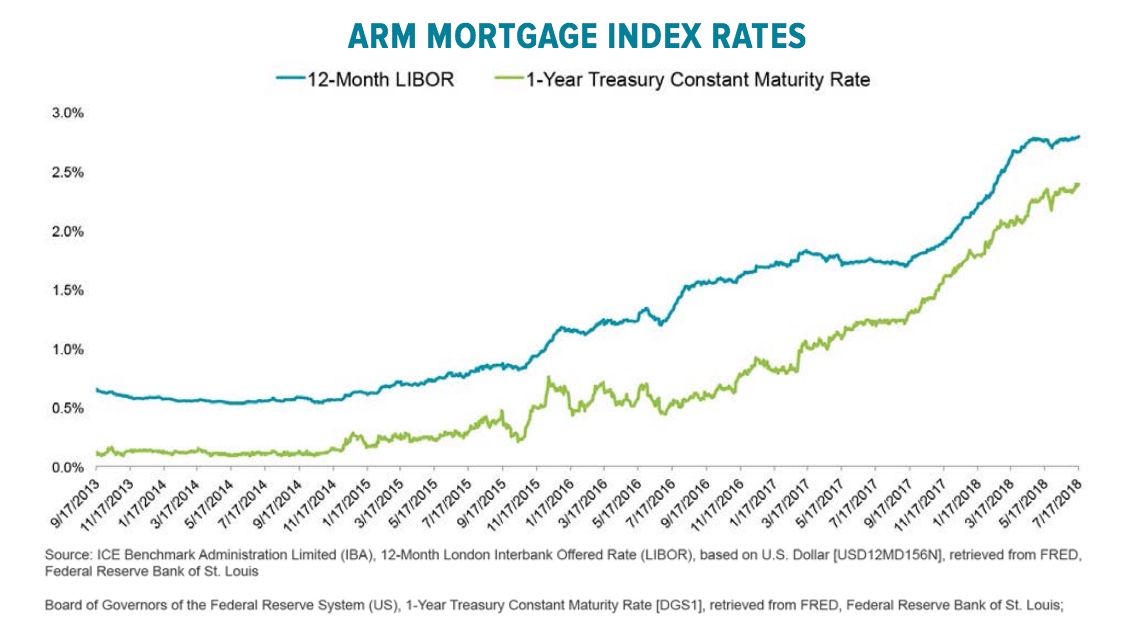

The Monitor also looked at how rising short-term interest rates may be impacting adjustable rate mortgages (ARMs). While they have made up only a small share of loan originations in recent years, never exceeding single digits in the Mortgage Bankers Association's weekly applications survey since at least 2014, there may still be many such legacy loans in place. The ARM subset of borrowers had been the beneficiary of downward reductions in their rates and payments following the financial crisis, but that's no longer the case.

Black Knight found that 1.7 million borrowers have seen their monthly mortgage payments increase by an average of $70 over the past 12 months. The majority of ARMS are set to adjust according to either the LIBOR or the Constant Maturity Treasury (CMT) and both have risen, resulting in the average rate on a post-reset ARM rising by more than .5 percent over the past 12 months and nearly .75 percent over the past two years. This has pushed the average post-reset ARM interest rate to more than 4.5 percent, putting it within an average 16 basis points of where these loans started out, some of them more than 10 years ago.

There is an additional factor in that most of the 12-month increase in the LIBOR occurred early this year and has not yet affected many resets. Black Knight looked at what would happen at the next reset to affected borrowers if LIBOR and CMT rates remain where they were in June. It estimates that there are 1 million loans that will increase at their next reset, with an average rate increase of .67 percentage point and more than an $80 bump in the monthly payment. Borrowers who have already had a reset are likely to see their rates rise above their origination rate at the next adjustment.

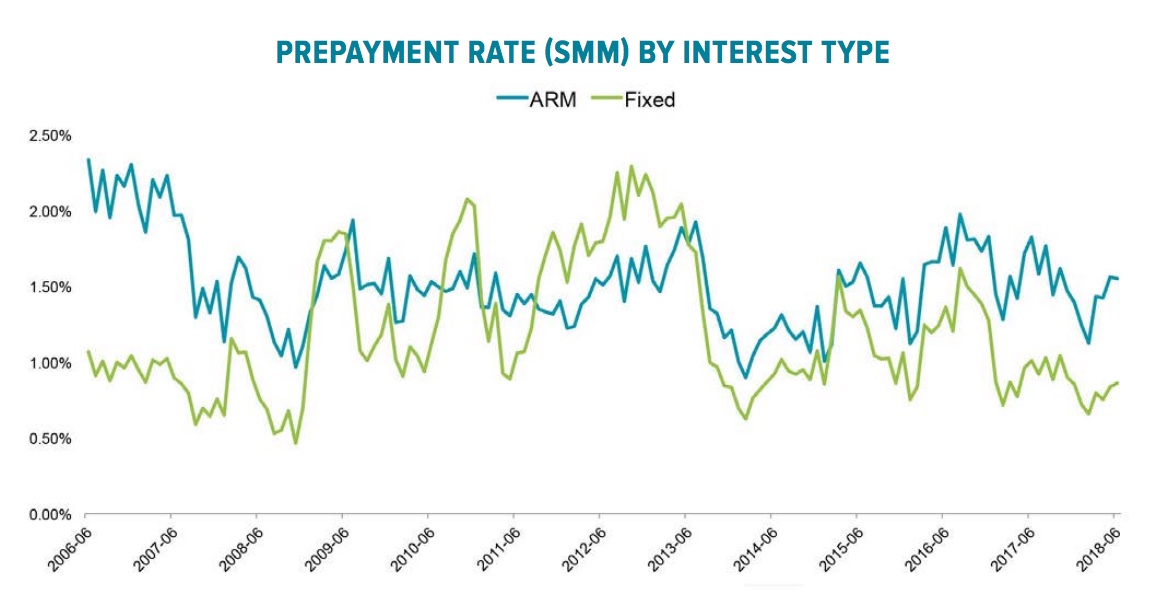

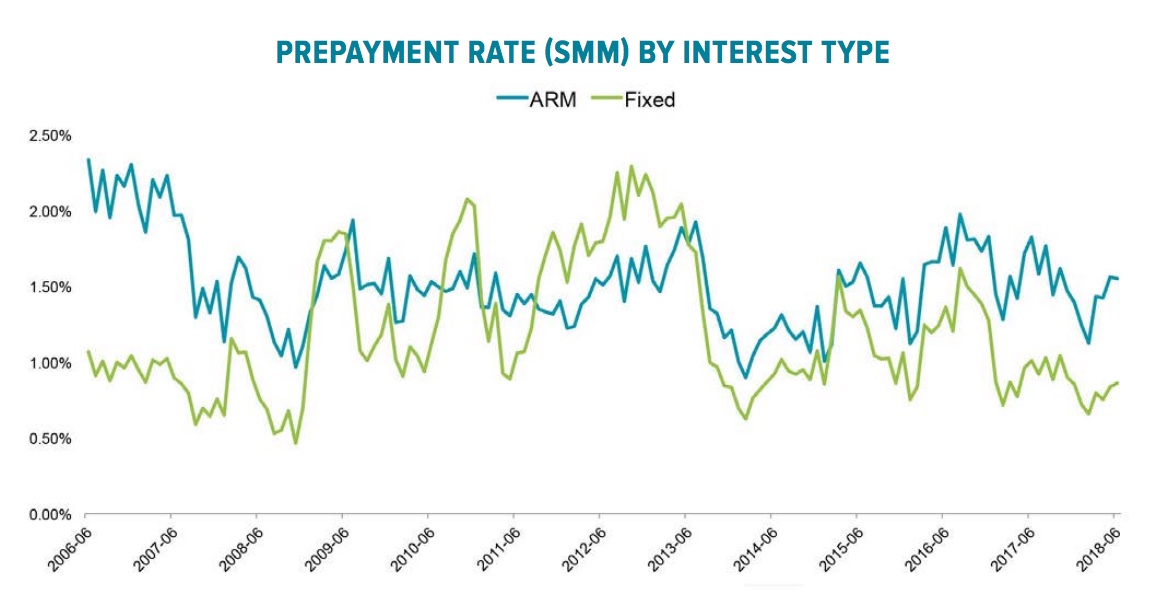

Black Knight said the increases have not yet led to any measurable increase in delinquencies among the affected loans, but they do appear to have been affecting prepayment rates. ARM borrowers have been prepaying at a 72 percent higher rate than their fixed-rate counterparts over the last year, and in April that differential reached 89 percent, the largest in nearly 10 years.

The prepayment rate among older ARMS, originated between 2004 and 2008, is up more than 40 percent over the last two years while prepayments among fixed-rate loans declined 7 percent. Black Knight said that not only are rising short-term rates moving ARM borrowers to refinance, but also to sell their homes; those prepays are up by 50 percent. Prepayments occasioned by refinancing are up 50 percent among rate/term borrowers and cash-out driven prepayments have doubled. The company said inferences can be made about future originations passed on the refinancing; 75 percent of those refinancing out of ARMs are choosing fixed-rate products.