It shouldn't be news to anyone that the homeownership rate of the Millennial generation continues to be anemic. While it has improved slightly since 2015, the Urban Institute's (UI's) new research shows that, at that point it was 37 percent, 8 percentage points lower than the homeownership rate of Gen Xers and baby boomers at the same age. This translates into 3.4 million fewer homeowners among these 75 million young adults.

UI researchers Laurie Goodman, Jung Hyun Choi, Jun Zhu, writing in the Institute's Urban Wire blog, say that demographic and lifestyle choices, delayed marriage, increasing diversity, have played a role in the decline, it is the economic environment that has been most determinative.

They cite three external factors that are hampering the generation, most of whom turned 25 after the housing crisis, from becoming homeowners; high rents, a limited number of available homes, and even now, tight credit standards.

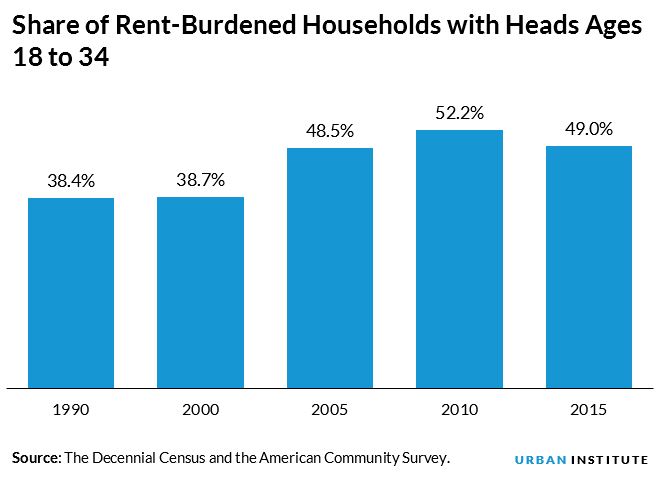

Even with the low downpayment requirements now available, a 3 percent downpayment plus closing costs requires a lot of cash. Paying high rents makes the goal of saving for a home purchase even harder. UI says the proportion of rent-burdened households, those that pay more than 30 percent of their household income for rent, increased among households headed by those 18 to 34 from 38.4 percent in 1990 to 49.0 percent in 2015.

The authors say that even a 1 percent increase in the rent-to-income ratio of a household reduces the likelihood of homeownership by 0.07 percentage point. Therefore, if the ratio increases from 30 to 50 percent it cuts down on the likelihood a household can buy a home by 12 percentage points.

Rents have increased more in cities where the housing supply is limited. Those tend to be cities with the largest supply of jobs and consequently those that have been most attractive to Millennials over the past decade.

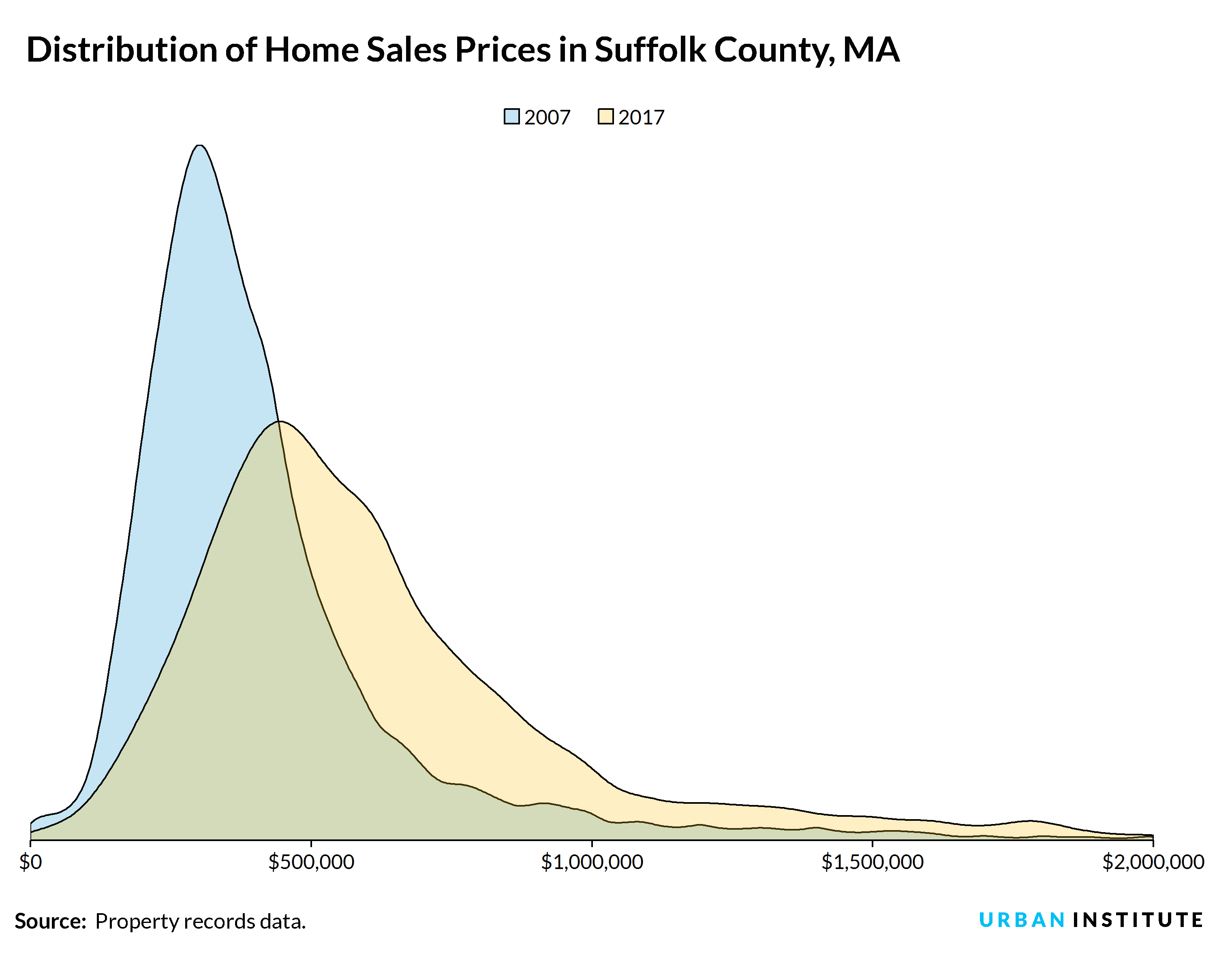

There is increasing concern over the low inventories of homes for sale, especially those in the lower price tiers where first-time buyers are most able to buy. Since the housing market crisis, the number of new housing starts has fallen significantly, from 2.0 million units in 2005 to 550,000 units in 2009. Even now, nearly 10 years later, housing starts are only at the rate of about 1.2 million units, not even at 1960s levels. The estimated difference between net new housing supply and net new household formation or demand in 2017 was almost 350,000 units.

Both purchase prices and rents have been affected by the lack of housing. The UI researchers did a distribution analysis for San Francisco, inner city Boston, and its inner and outer suburbs. In all they found a shift in the distribution of supply toward higher prices. A smaller share of sales is occurring at the lower end of the price spectrum, where millennials are most likely to buy. For example, in Boston proper (Suffolk County), the $1 million home became more common between 2007 and 2017 and the $2 million home has become the next frontier. Yet UI says metro Boston is in the middle of the pack on its bubble watch list, sitting at 20th out of 25 areas. San Francisco is even more extreme, with the peak of the distribution bell occurring just under $1 million.

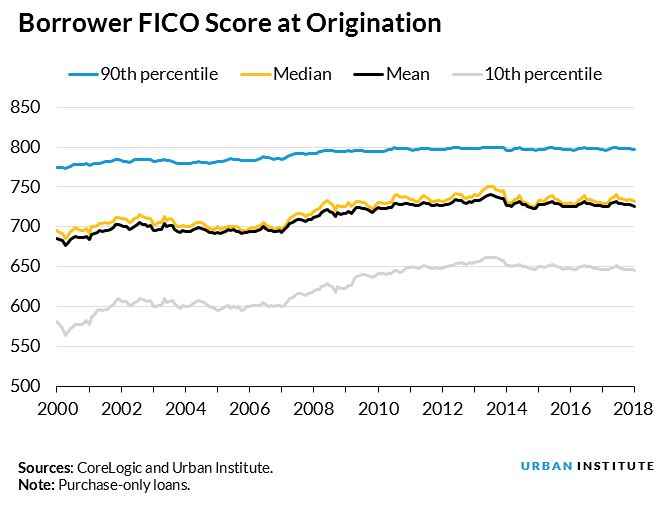

Finally, Millennials are confronting stringent credit standards. The overall credit score for mortgage holders has increased from 695 in January 2000 to 738 in April 2018 while that of the bottom 10th percentile increased from 595 in January 2000 to 648 in April 2018.

Younger adults tend to have lower scores so the increase at the lower end of the distribution particularly affects Millennials. They have a median score of just 640, nearly 100 points lower than the median of new mortgage originations. Even credit scores in the top 25th percentile among millennials are lower than the median credit score for new mortgage originations.

As homeownership is considered to be highly beneficial for most families, offering a stable place to live, a hedge against inflation, and a way to build wealth, the delay or loss of homeownership among Millennials could have a significant, negative impact on them. Further, UI research also suggests that parents who own have a significant influence on whether or not their children do, so the low millennial homeownership will likely have a multigenerational impact.

The authors conclude that, with increasing life expectancy and pensions a thing of the past, millennials will need to be even more financially prepared for retirement than previous generations. Getting a late start on building housing wealth will not help.