Bank of America/Merrill Lynch says its official outlook for the economy is neither that of a Bull forecasting a cyclical surge or a Bear's view of secular stagnation. Rather, the company says it is looking for a low growth recovery.

Chris Flanagan, head of the company's U.S. Mortgage and Structured Finance Research has written a paper titled Mortgages: the big picture in which he lays out a lot of theories and a lot of projections.

Looking ahead to the end of 2015 Flanagan first sees only minimal growth in Real GDP. From its 3.1 percent level in the fourth quarter of 2013 he sees it dipping to 2.1 percent this year and ending 2015 at 3.2 percent. From the end of 2012 to the end of 2015 the Core PCE (personal consumption expenditures price index excluding food and energy) will have risen only a net 0.1 percent, from 1.6 to 1.7 percent. The Federal Funds rate may as much as quadruple in the next year but still will not cross above 1 percent and he projects that the 10 Year Treasury Note rate, currently at 3.10 percent we rise to 3.75 percent. The only real indication of an improving economy will be unemployment which, from 8.1 percent at the end of 2012 he forecasts at 5.5 percent by the end of next year, falling even further after that.

What happens to the economy of course is critical to what will happen to interest rates and thus to the mortgage industry. Flanagan points to some current indicators and what they might mean for the industry looking ahead.

A declining unemployment rate, is usually accompanied by a flatting yield curve and he sees the spread between 2 year and 10 year at zero by the time unemployment hits 4 percent at the end of 2016. Both credit and volatility tend to be, as Flanagan puts it, "well behaved in flatteners."

The demand for non-mortgage types of credit, commercial, corporate, and consumer, has returned more closely to normal in the wake of the recession. But both the supply of and demand for mortgage credit remain very weak and for several reasons.

Homeownership peaked in the fourth quarter of 2004 at 69.2 percent then began a gradual decline that brought it down to its current 64.7 percent. Even after that decline began credit continued to expand and did not peak until the second quarter of 2006. At that point the Mortgage Bankers Association says its recently introduced Mortgage Credit Availability Index would have been at 868.71 percent. It has been coasting along in the neighborhood of 100 since late 2007 or early 2008.

Flanagan blames this tight credit on the last five years of regulation, litigation, and government intervention.

The lack of a normal mortgage market, especially tight credit, is having a major impact on most aspects of residential real estate - some negative and some positive. While new home sales have suffered, prices have risen, yet affordability has remained high.

Flanagan sees the lack of supply and demand as indicating a need for further monetary accommodation as Quantitative Easing (QE) winds down although a zero interest policy is expected to continue through the second quarter of next year.

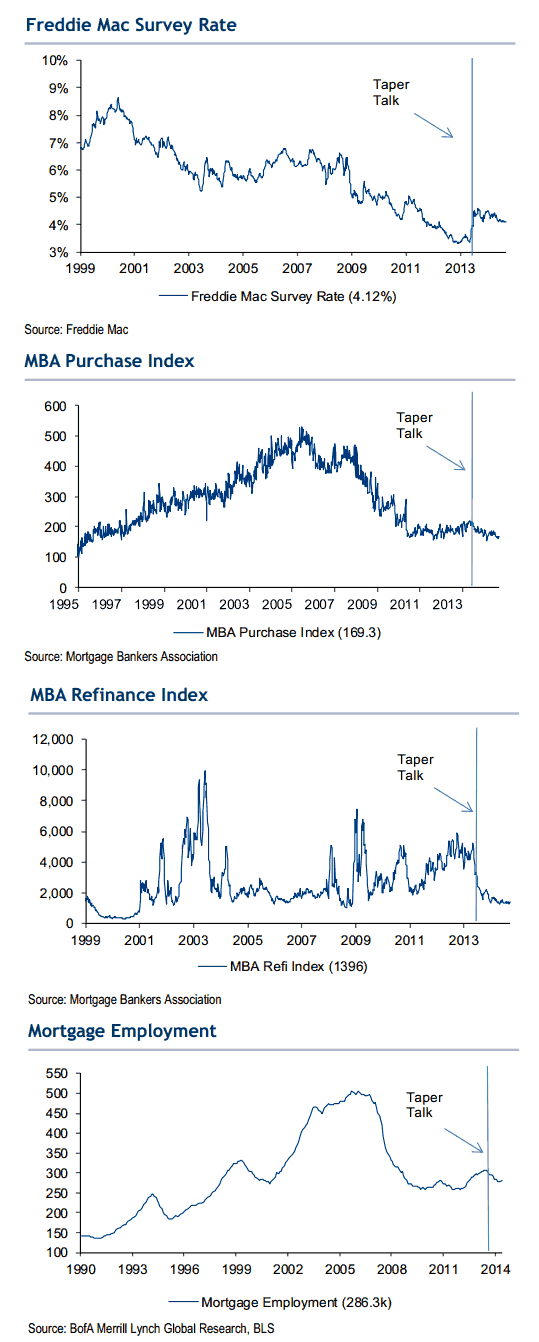

Like loose lips sinking ships Flanagan shows that even talk about the Federal Reserves' intention to taper QE had an impact on interest rates, mortgage origination and employment in the industry.

Homeownership grew quickly in the 1990s, the most precipitous increase can be dated to a call from President Clinton for a national homeownership effort in 1994, and as might be expected the volume of purchase mortgage applications increased right along with it. The 2004 peak in the former closely approximated the peak in the latter and both have proceeded down in near lockstep.

The relationship isn't quite as close between the decline in homeownership and the growth and retraction in GSE portfolios. Portfolio growth tracked closely from the mid 1980 through the peak and during the first few years of homeownership decline. But the portfolios did not begin to decline in earnest until the GSEs were mandated to liquidate them as a condition of their federal conservatorship. With those portfolios down to slightly more than half their size in 2008 Flanagan says this could be an opportunity for real estate investment trusts (REITs) to fill the void.

Declining homeownership equals declining home purchase mortgages and that, together with the declining GSE portfolios, means a much smaller investment in MBS, especially Agency MBS. The paper points out that of the 5.47 trillion in U.S. fixed income gross issuance in 2008, 20.8 percent was Agency MBS and 16.7 percent was Treasury notes. With a substantially smaller issue ($4.38 trillion) in 2014 the Agency MBS share has dropped to 13.1 percent while Treasury has 31.6 percent.

Flanagan says the stable and low MBS spreads along with low volatility seem to be the new normal in the mortgage world and again he points to the current environment as providing opportunity for REITS as the Federal Reserve and the GSEs no longer continue to grow their portfolios.