Americans are staying put, both in their homes and in their jobs. The two appear to be related but which is the driving force?

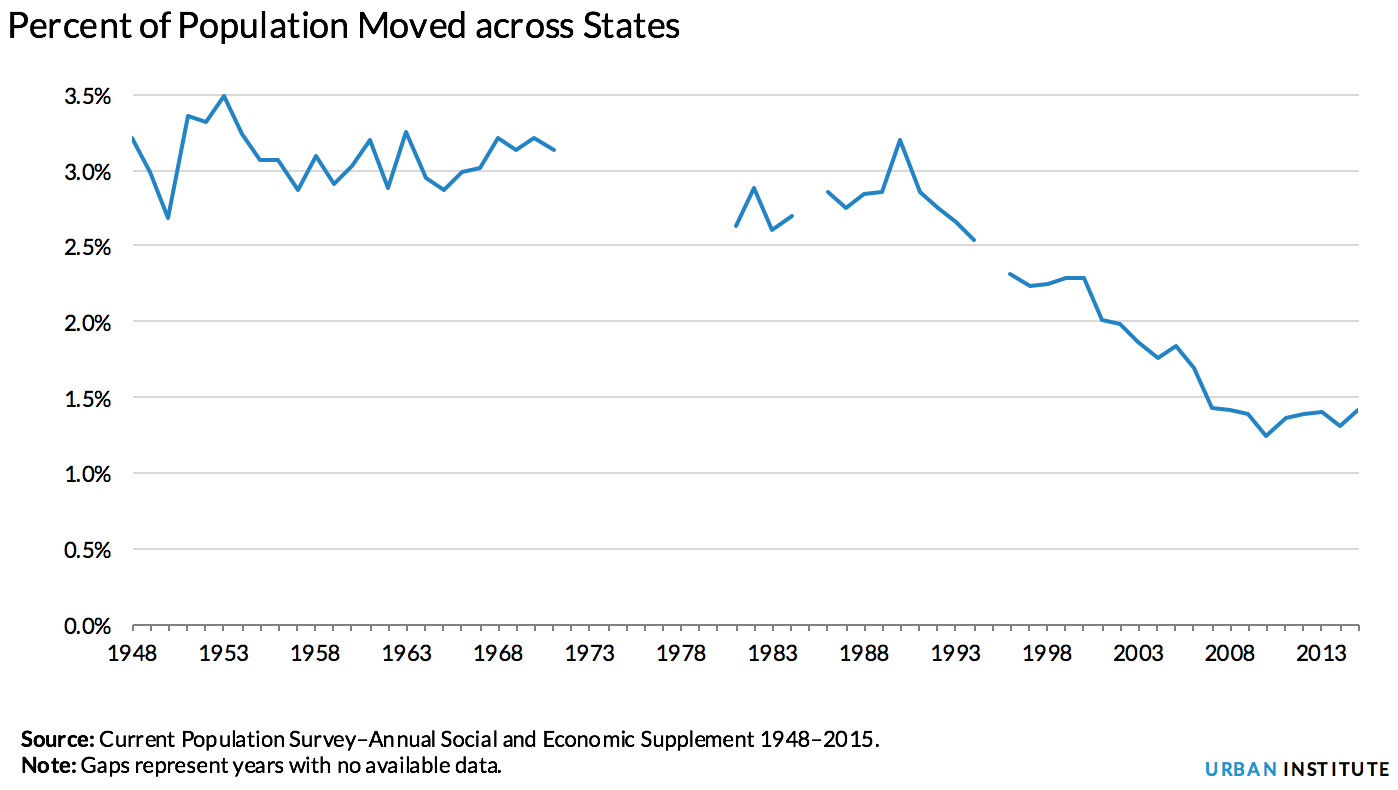

In a recent Urban Institute blog researcher Bhargavi Ganesh points to the decreasing incidence of state-to-state migration, a trend that started in 1990. Her cites research from Raven Molloy of the Federal Reserve that shows interstate movers dropped from nearly 3 percent of the population in the 1980s to less than 1.5 percent in the five years that ended in 2015. This has happened "despite technological advances, increased immigration, and higher education levels, all factors one might expect to boost migration."

Urban Institute researchers say it appears that the decreased mobility is related to the labor market rather than demographic or socioeconomic changes. Among the results is an eventual impact on the mortgage industry.

When one looks at data on homeownership, showing a decline in all but the oldest age groups, it might appear that the aging population may account for the decline in interstate migration since the elderly and homeowners are both less likely to move. Yet the Federal Reserve data shows that migration has been declining for all age groups and for both renters and homeowners. It has also been declining irrespective of gender, education, race, income, marital status, employment status, geographic location, and whether individuals are foreign or native born.

Post-recession housing affordability and tougher land-use regulations can also be discounted as Malloy's research shows the decline in mobility is substantial even in states where houses remain affordable or where land-use regulations are relatively lax. That leaves the labor market as the causative factor.

Molloy found that the fraction of people changing occupations, industries, and employers also slowed between 1990 and 2011, that trend falling in roughly the same time frame as that of the decrease in migration. In addition, the states with the largest declines in job transitions also have the largest declines in migration rates.

But, the chicken and egg question; are job market conditions lowering mobility or does lower mobility cause job market changes? Molloy concludes it is the former because long-distance moves are most often job related. Also, the migration flows are too small to explain the job market changes since the percentage of the population that changed employers fell about 4 percent, while the percentage of the population that changed states fell only 1 percent.

What does lower interstate migration mean for the mortgage market? Ganesh refers to research from Sam Khater, an economist at CoreLogic. Khater says fewer people moving means fewer mortgages being originated but at the same time leads to fewer defaults as borrowers have more time to build equity as a buffer against an economic downturn.

Lower migration can also increase demand for second liens, as homeowners decide to renovate the homes they plan to live in for a longer time. Decreased mobility could also decrease demand for mortgage products that minimize interest rate risks, such as fixed-rate mortgages or longer-term adjustable-rate mortgages.

Ganesh says it is important to understand the reasons behind the decrease in mobility because it will help us understand if there are barriers preventing people from moving to obtain the jobs they want and to live where they may wish to live. "And understanding the impacts of these changes helps ensure that our policies recognize and address reality."