Two George Washington University professors have called current discussions and proposals to curtail FHA's low down payment loans an overreaction. Robert Van Order, Professor of Finance and Anthony Yezer Director of the Center for Economic Research, both at George Washington University's School of Business are authors of a multi-installment FHA Assessment Report which seeks to identify the factors that are determinants of mortgage risk, i.e. down payments, credit scores, and debt-to-income levels, to ensure that FHA doesn't layer on excessive risk.

In the third installment released on Monday the authors state that, if all we knew about loans was their down payment we should want to control it closely but mortgage lending is more complicated than a single dimension can capture and credit risk is determined by a combination of factors with tradeoffs among them. "It is possible to do low down payment lending profitably, but not in a vacuum, and it need not be much riskier than high down payment lending," they said.

The third installment looks at three specific issues.

- The trade-offs among readily observable loan characteristics.

- The risk of different loan types as measured by their variability or sensitivity over the housing cycle.

- Factors that are not so readily observable such as the source of the down payment that are important and need to be considered when evaluating the relationship between LTV and future default.

While there is evidence that lack of equity in a property is a determining factor in predicting default, it may not mean that loans are riskier for this reason alone. Historically, low down payment loans tend to have higher default rates, however neither this or higher foreclosure rates are necessarily the same as higher risk. Risk is about deviations from the mean, not the size of the mean. High LTV rates are priced by the FHA and if defaults turn out as expected, profits will also be as expected with higher prices offsetting increased losses. The risk question is how unstable profits are when there are shocks to default rates.

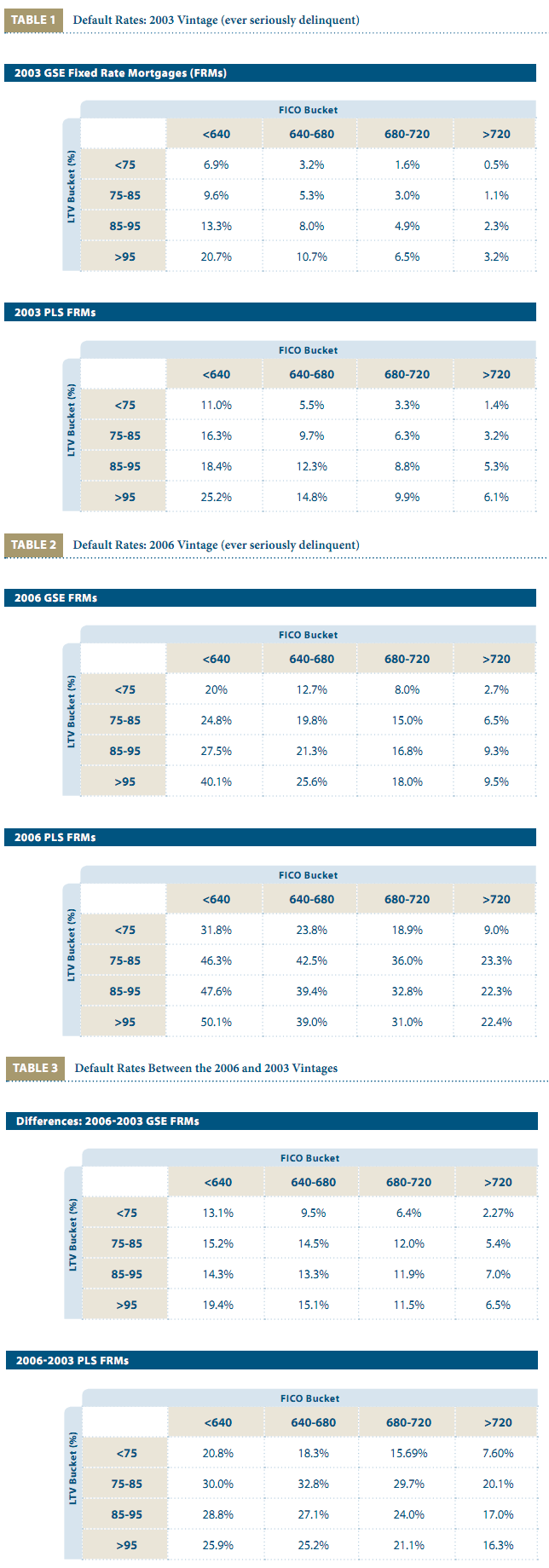

Both high and low LTV loans had unusually high losses during the recent housing crisis so it is necessary to compare the increases in losses for different types of loans and loan underwriting characteristics. The following tables look at Fannie Mae/Freddie Mac (GSE) loans and private label securities (PLS) loans originated in 2003 when the economy was strong and there were three years of increasing home prices ahead and in 2006 when prices had started to decline. The authors examined the default rates (defined as loans that were ever considered to be in "serious trouble", i.e. 90+ days delinquent) within matrices defined by four ranges of LTV and four categories of FICO scores.

(See tables 1 - 3 below)

In 2003 higher LTV loans had higher defaults if the FICO scores were held constant but not if the FICO score varied. High LTV loans with high scores had about the same default rates as low LTV rates with low scores. There is a trade-off among the two variables so that the worst combination is a high LTV with a low credit score.

Economic conditions also play a role. The 2006 era loans had worse defaults in every category than those from 2003 and this with only three years exposure compared to six for the older loans. The original channel matters as well; where the other variables are held constant there was a higher default rate for PLS loans than those associated with GSE, especially in the 2006 vintage. When looking at the data indicating the difference in rates between the 2003 and 2006 vintage, it was the seemingly safest, lower LTV loans that performed disproportionately worse indicating how far from the norm things vary when conditions change, especially when they get worse. What did help with these loans were high FICO scores and the avoidance of risk layering.

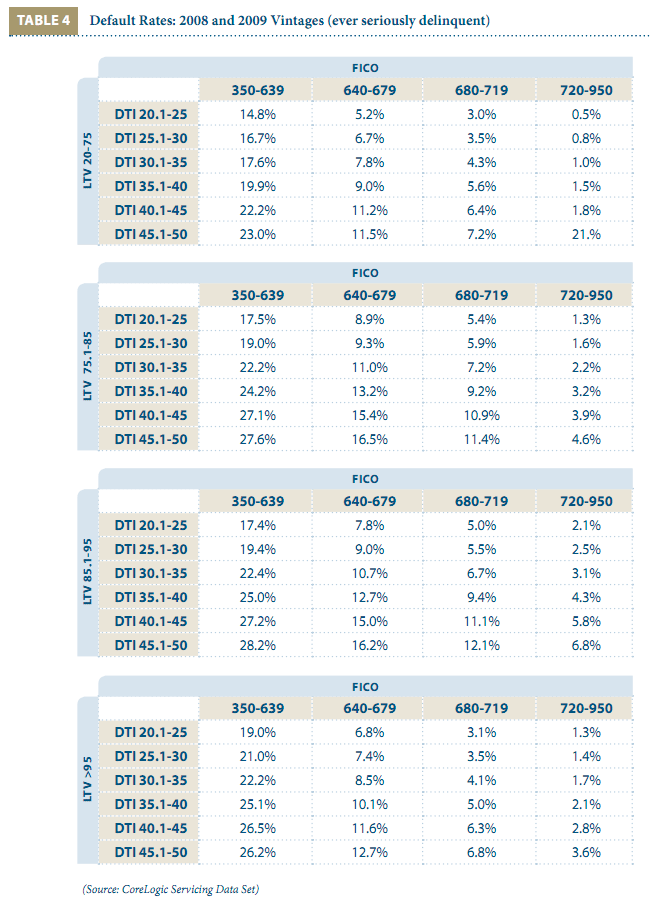

(See table 4 below)

When another layer of risk is added, in this case debt-to-income rations (DTI) the risks of layering grow more apparent. Mortgages with higher DTI ratios default more frequently, and in the distressed period LTV was a much less important protection against default than were credit score and DTI. "There was much more variation moving from 'southwest' to northeast' parts of the matrices in the table, holding LTV constant than from moving from one matrix to the other holding FICO and DTI constant."

The authors maintain that FHA can remain sound and fulfill its dual missions as guarantor of last resort in a significant housing crisis and insuring access to mortgage credit for first-time and minority home buyers, but the reality is that political oversight limits its flexibility to adjust to trade-offs in risk management. "Historically, FHA has responded to challenges only after significant lags, during which losses and inefficiencies were rampant. The authors cite the current FHA guideless that allow it to finance up a 96.5 percent LTV to a buyer with a 580 FICO score and a 48 percent DTI even while other lenders have acknowledged the layering associated with such allowances and have tightened their guidelines.

The report also weighs what the authors call "things you can't see," the risk presented by seller-funded down payments and seller closing cost assistance. In the former instance the seller would not contribute to the down payment if he were otherwise able to sell the home and so there must a compensating increase in sales prices above what other buyers were willing to pay. Therefore the buyer is, by definition, paying more than the home is worth. Other studies have found that seller assistance is equivalent to the comparable increase in LTV when considering default rates; i.e. an LTV of 98 without seller assistance had the same default rate as a 95 percent LTV with 3 percent seller assistance. While the practice of allowing sellers to provide such a large share of the down payment has been ended, current buyers are paying the price for its former existence. A recent audit which led to increases in premiums for buyers linked the near disastrous decline in the Mutual Mortgage Insurance Fund to two factors; the weakening of the housing market and the concentration of loans receiving payment assistance from non-profits.

The conclusions of the two earlier reports in the FHA Evaluation series are worth mentioning. The first report issued in February 2011, analyzed FHA current policies including its loan limits, mission, and market share. The main finding was that FHA had served the market well during the housing crisis and that its mortgages , while continuing to have high default rates than conventional loans (with compensating fees) did not experience as large a surge in defaults as did conventional and other mortgage types.

The analysis found that the 2008 expansion of loan limits gave FHA the ability to serve nearly 97 percent of the available low down payment market and FHA's market share increased from 6 percent in 2007 to more than 56 percent in 2009. FHA-insured loans with balances over $350,000 had default rates that were approximately 20 percent higher than those for smaller loans. "Thus, it is not clear than enlarging FHA market share by maintaining high loans limits is a good way to recapitalize the insurance fund; nor is it clear that FHA is flexible enough to operate for long periods of time with a large market share."

The second report noted that the FHA loan limits in place at that time were larger than necessary to serve its targeted market of first-time and low-to moderate-income borrowers. The report demonstrates that FHA could still serve 95 percent of its historic targeted market even if the maximum FHA loans limits were reduced by nearly 50 percent, that is to $200,000 in low cost markets and $350,000 in high cost areas. Further, FHA only needs to maintain a market share of between 9 to 15 percent of total originations. The report also found that the anticipated loan limit reductions (which went into effect on October 1) would have affected only 3 percent of the loans endorsed in 2010.