While there has been a lot of talk since the recovery took hold about the lack resiliency in the residential construction sector, the issue is now moving from an academic discussion to one on the verge of alarm. As Freddie Mac's Economic and Housing Research Group writes in the company's Insights blog, "The inadequate level of U.S. housing supply is a major challenge facing the housing market in 2018 and likely for years to come."

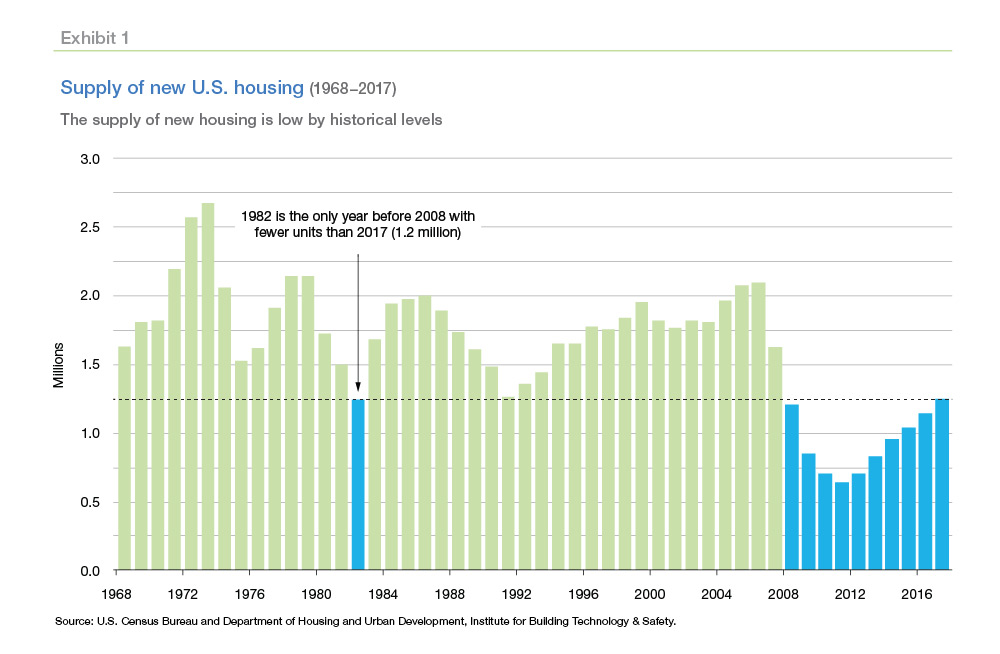

The Insights' authors, Sam Khater, Chief, and Len Kiefer, Deputy Chief Economists, and Ajita Atreya and Venkataramana Yanamandra, both senior quantitative analysts, estimate the U.S. needed 370,000 more than the 1.25 million units that were added to the stock in 2017 to satisfy demand. In the forty years starting in 1968 to the start of the Great Recession in 2008, there was only one year in which fewer new housing units were built than in 2017, even as the economy grew and demand was rising.

Depending on a variety of assumptions, the shortfall could actually range from 0.9 million to a high of 4.0 million housing units. "If supply continues to fall short of demand, home prices and rents are likely to outpace income, and household formation will fail to reach potential," the article says.

Housing costs are usually cited as the most significant factor keeping young adults from forming households and from buying a house. Strong demand and weak supply have driven up housing prices sharply, which acts to balance supply and demand but is also keeping many young people in shared living arrangements or remaining in their parents' homes.

Supply and demand aren't the only culprits. Since 2010 the cost of land has averaged about 23 percent of total home building expenses but in some markets, especially on the West Coast, land can account for as much as 70 percent. Building regulations and zoning restrictions add to this and the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) estimates that these costs increased by 29 percent between 2011 and 2016.

Add to this the labor costs arising out of a shortage of skilled workers. NAHB estimates that unfilled jobs in construction reached a post-crisis high this year. Non-cost factors such as local opposition to development are also constraining construction.

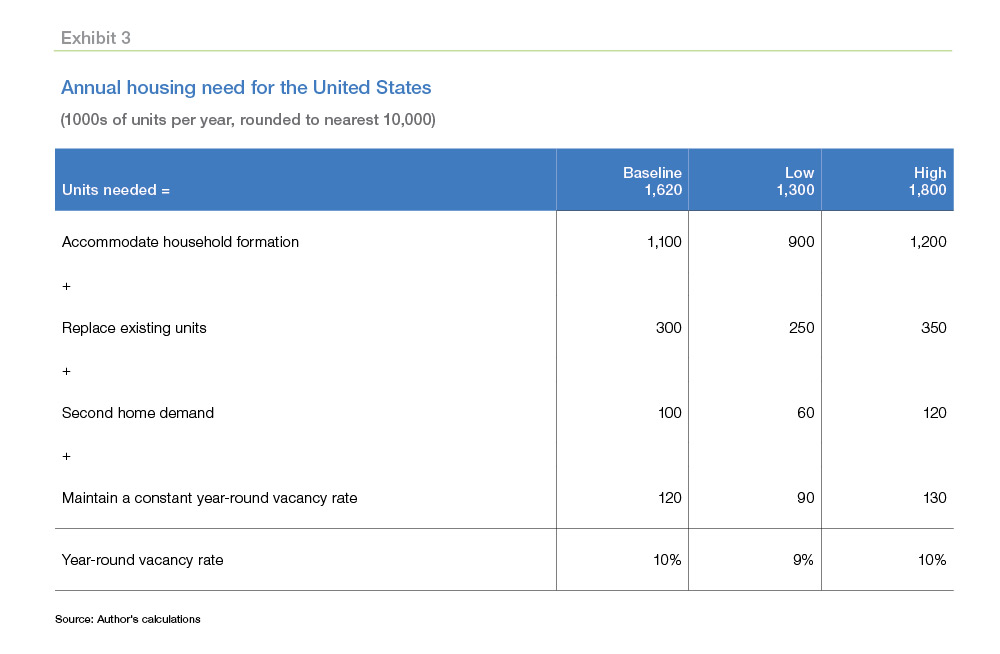

On the other side, three factors drive the need for housing construction: growing demand from a growing population; the need to replenish existing stock; and the requirement for vacant units in a well-functioning market.

Nearly 90 million U.S. residents were between 15 and 34 years old in the United States in 2016, 6 million more than those aged 35 to 54. The age of the median first-time home buyer is now 31, so these young adults comprise a large share of the first-time home buyer population and therefore drive demand higher.

Because many young adults live with parents or roommates there is a pent-up demand for housing. Even though research shows that demographic shifts and other long-term trends reduce household formation rates, the big hurdles are associated with housing costs and the labor market. If the economy remains strong and housing costs moderate, then household formation for young adults could significantly increase. The authors estimate that young adults (ages 15 to 34 in 2016) will add about 20 million new households over the next decade. "And those households will need a place to live," they say.

Young adults could buy homes from their elders, but Americans over age 55 aren't ready to move out yet, preferring to age in place. Better health and education mean this could take a while. Freddie Mac estimates the U.S. net household growth needs to average around 1.1 new housing units to meet the growing population. "Eventually as the Boomers age out of the housing market and young adults are replaced by the smaller Generation Z, the growth in households will moderate somewhat, though the date for that moderation is well into the next decade."

Add to population growth the fact that aging housing stock must eventually be replaced. The Census Bureau estimates the U.S. housing market needs to add approximately 350,000 units per year to replace units lost to age or other hazards.

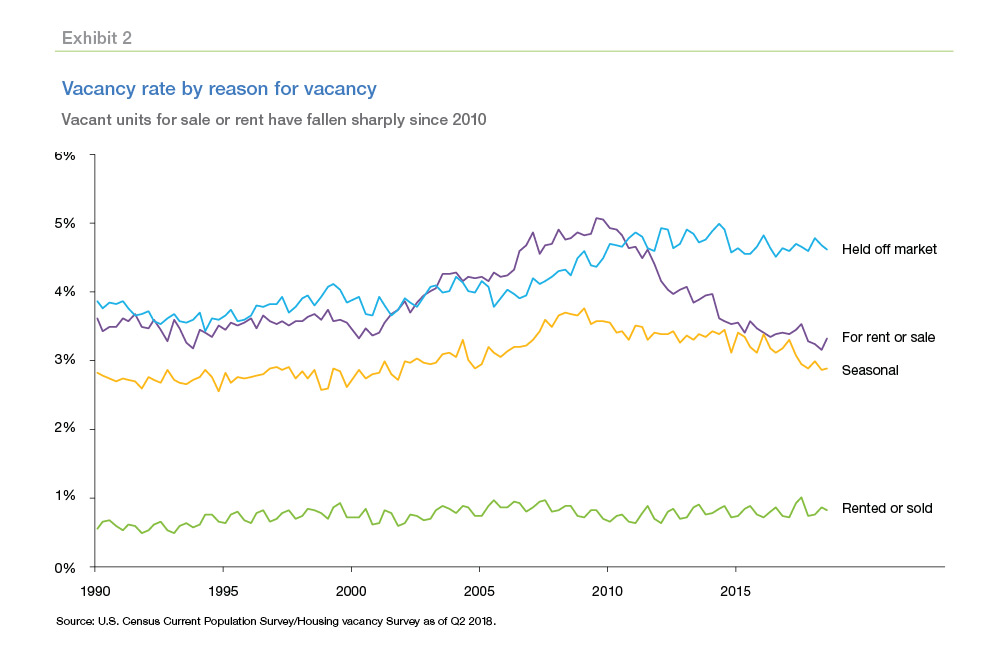

A well-functioning housing market also needs vacant properties for sale and for rent. These increase liquidity in the market, enable prospective buyers to find a match, and give prospective sellers confidence to list their home for sale. Too high of a vacancy rate reflects a stagnant market, while a too low rate reduces the efficiency of the marketplace. The vacancy rate has declined sharply since 2010, mostly due to lack of inventory.

About 3 percent of the U.S. housing stock is seasonally vacant, usually meaning vacation property. The demand for second homes adds up to approximately 100,000 units per year and NAHB estimates that the stock of these homes rose by 120,000 units annually from 2009 to 2014. A growing economy and wealthier households will shore up the demand at a similar pace for years.

Freddie Mac estimates that the U.S. needs to add 1.62 million units annually to meet demand; 1.1 million to accommodate household growth; 300,000 units to replace depreciated stock; 100,000 to meet second home demand; and 120,000 units to provide enough vacant homes to maintain an efficient marketplace. This is their baseline. The true long-run housing demand is uncertain, therefore Exhibit 3 also presents estimates based on low and high scenarios although there is considerable uncertainty around each. However, even the low estimate (1.30 million units per year) exceeds the current rate of housing construction (1.25 million units in 2017)-meaning even under a low estimate, at least 50,000 American households each year can't buy or rent a home because it hasn't been built.

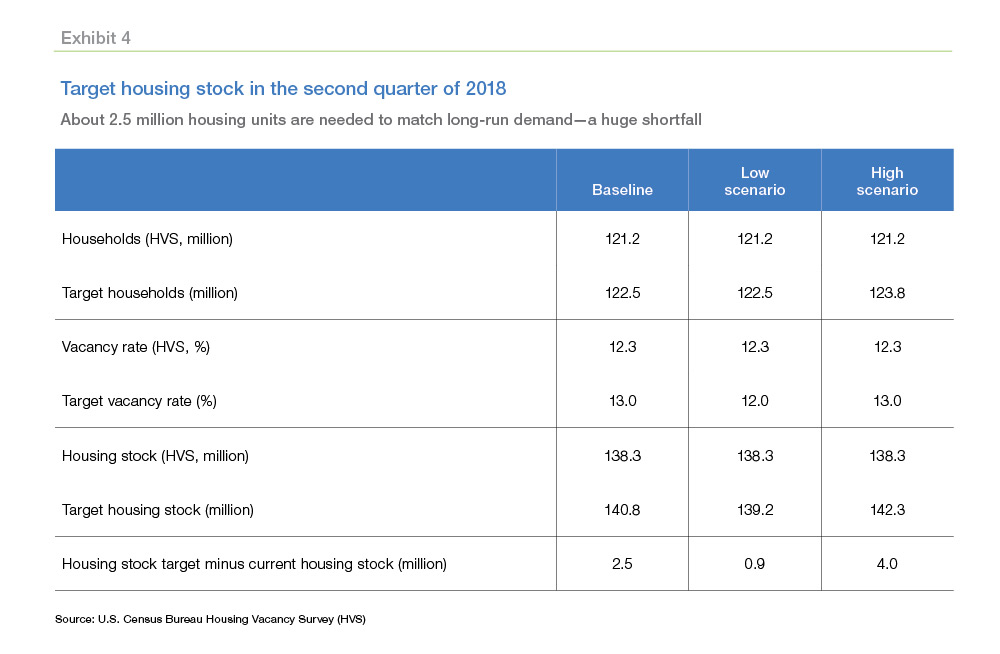

The economists have focused on a one-year shortfall, but residential construction has been lagging for nearly a decade. As of the second quarter of 2018 the U.S. economy appears about 2.5 million units shy of long-term demand.

As stated earlier the year-round vacancy rate should be around 13 percent and was 12.3 percent in the second quarter of 2018, so it would seem that the housing market is roughly balanced. However, this does not account for pent-up housing demand.

The Census Housing Vacancy Survey (HVS) estimates there were 121 million households in the second quarter. As discussed, several factors impact household formation; housing costs, income, employment, education, marriage and children, race, and geography. Freddie Mac identified housing costs as the biggest impediment, followed by labor market outcomes. Under the assumption of no constraints from these two factors, the number of households could range between 122.5 million in the baseline scenario and 123.8 million in the high scenario.

To accommodate these larger numbers and maintain a 13 percent vacancy rate, the housing supply would need to increase by 2.5 million units, expanding from 138.3 million units to 140.8 million units in the baseline, or as much as 4.0 million units to 142.3 million in the high scenario In the low scenario, vacancy rates fall to 12 percent and the housing supply only needs to expand by 900,000 units to 139.2 million units.

To bridge the gap between the current housing supply and future demand, housing construction will need to accelerate. First, the annual gap of 370,000 units currently being undersupplied relative to long-term demand must be filled. Then, the housing market will need to supply excess units for some time to bring the housing stock up to its target level.

Another problem is the unevenness of the market. Year-round vacant homes that are off market have been increasing. As the U.S. population has drifted south and west, the populations of many older cities in the Midwest and Northeast have declined sharply and their vacancy rates have soared. Even where employment growth has been strong and long-run housing supply elastic, Texas, for example, shortfalls in skilled construction workers and available lots have held down construction. Even in traditionally elastic housing markets, home prices are rising rapidly. well above long-run averages.

Over time, the housing supply in high-growth but elastically supplied areas will expand, but in the interim, housing cost pressures may result in movement toward areas with lower housing costs. If housing demand shifts toward lower-cost housing markets that currently have available housing supply, the long-term vacancy rate could also begin to decline.

Freddie Mac's economists say they expect that housing construction will improve gradually but it will be at least a year before the level of building matches incremental annual long-term housing demand. To bridge the shortfall of total units, the U.S. housing market may need to supply more than 1.6 million units per year. Until construction ramps up, housing costs will likely continue rising above income, constricting household formation and preventing homeownership for millions of potential households.