(Much of the following is adapted from yesterday's coverage, but with additional charts and examples. As far as brass tacks go, if you got the message yesterday, today's version is just a little bit more of the same.)

Mortgage rates have been all over the map recently, both in terms of their movement and in their variation between lenders. The disconnects are so big as to require a deeper explanation.

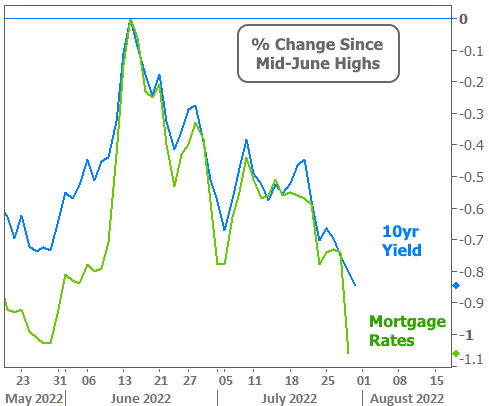

Let's quantify "big." Best-case-scenario rates for a conventional 30yr fixed are down about half a point from last week on average and more than a full point below the mid-June highs.

This is an exceptionally fast drop! In fact, it's a bit faster than the drop seen in the 10yr Treasury yield, a frequently used benchmark for mortgage rates.

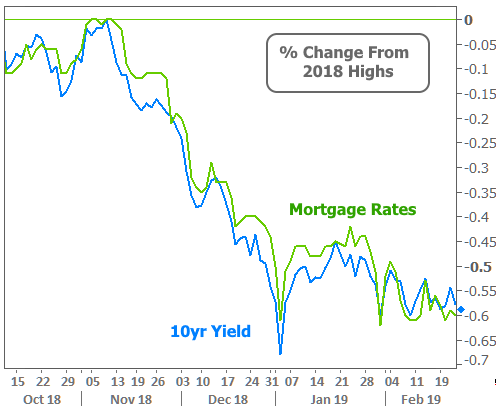

That makes it even more exceptional because the 10yr almost always moves faster than mortgage rates on the way down. Here's an example from the last time rates moved down from a long-term high:

So why are things different this time, and what's up with the ultra sharp drop over the past few days?

A word of warning: answering these questions requires guided tour of some high level concepts involving the bond market. If it's all a bit confusing, that's normal. We'll cordon off the most esoteric stuff in the six steps below. These provide the foundation for understanding what's going on.

Step 1: Mortgage rates are based primarily on mortgage-backed securities or MBS. As lenders originate mortgages, those mortgages can be "turned into" MBS and sold to investors who want to earn interest on mortgage debt.

Step 2: MBS have a coupon--which is the official rate paid out by a bond. Other bonds, like the 10yr Treasury Note, also have coupons.

Step 3: MBS have a price. Same story for a 10yr Treasury note. This is the price an investor pays to own $100 of that bond. A price can be higher or lower than $100. If I pay more than $100 for a bond with a hypothetical coupon of 4%, I'm technically earning less than a 4% rate of return because I paid more upfront. Coupons are periodically set in stone and the bond market moves by changing the price it pays for that coupon. The combination of price and coupon allows investors to know the actual yield associated with a bond. So when you see 10yr yields moving all over the place every day, the coupon never changed. Just the price.

Step 4: Unlike Treasuries, which change coupons only one per quarter, MBS coupons are offered in half point increments (i.e. 4.0, 4.5, 5.0, etc) and are always available for investors to buy/sell.

Step 5: In other words, investors have CHOICES TO MAKE when it comes to which MBS to buy. Investor demand for any given coupon can wax and wane for multiple reasons. In general though, when investors think the broader rate market has topped out or that rates will continue to move lower, they prefer to buy the lowest MBS coupons possible. As demand increases, those lower coupons gain value more quickly.

Step 6: Mortgage lenders have choices to make when it comes to choosing an MBS coupon to place their recently originated loans into. There are boundaries here. Any given MBS coupon is limited to mortgage rates that are between 0.25% and 1.125% above that coupon. e.g. a 4.0 coupon MBS is like a bucket that can only hold mortgages with rates of 4.25% through 5.125%.

Here's how all of the above has been playing out recently:

Falling rates and rising refinance demand can hurt investors' returns.

Investors who buy MBS see that rates likely topped out in June and have been heading lower ever since. Dour economic data added to that momentum this week. If rates continue to move lower, mortgage borrowers who recently closed will begin to refinance, effectively paying investors back too early, before investors have had a chance to earn much interest. In other words, early refinances cost investors money.

Investors try to get ahead of the game by buying lower coupon MBS (which are less susceptible to being paid off early due to falling rates). This drives up the value of those coupons.

Why would you ever care about a lower MBS coupon rising in value?

You might care more than you know. Mortgage lenders base their rates on several factors, but the price of the MBS coupon associated with those rates is the biggest consideration because most lenders turn your loan into MBS in order to sell it to investors.

Sounds simple enough, but again, MBS coupons can hold rates in a range from 0.25% to 1.125% above the coupon (remember 1.125%... we'll be using it in a moment). So a mortgage lender has a choice to make. Any loan they close can be slotted into one of two MBS coupons.

Lenders Like Making Money Too.

We talked about how investors shift their buying habits to make more money. This leads directly to lenders shifting their selling habits to make more money! Let's use a real world example from this week to bring us back out of the rabbit hole:

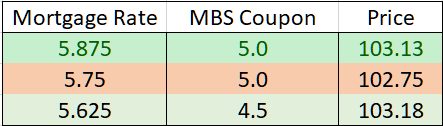

- Rates were in the mid-to-upper 5% range last week.

- A rate of 5.75% is too high for an MBS coupon of 4.5.

- A rate of 5.625% is NOT too high for a 4.5 coupon (4.5 + 1.125 = 5.625)

- Investor demand made 4.5 coupon MBS prices higher than normal compared to 5.0 coupon prices.

- This meant that lenders selling MBS actually made more money selling a 5.625% loan than a 5.75% loan!

- Note: the rate still factors into the profit equation. In other words, with a high enough rate, a 5.0 coupon can be more profitable than a 4.5 coupon, but not until moving at least 0.25% higher in rate. Here's an example comparing rates, coupons, and relative prices from a lender who makes more money by giving you 5.625% as opposed to 5.875:

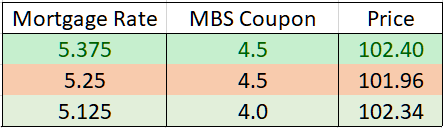

Moving down to the next MBS intersection, we find a similar scenario with 5.125% and 5.375%.

Perhaps more important than 5.125 being roughly as profitable as 5.375 to your lender is the fact that there's only 0.79 in price separating 5.875% and 5.125% (103.13 - 102.34).

A 0.79 improvement in the price of MBS is very large, but it's the sort of thing that happens during the course of a single day every now and then, and over 48 hour time frames quite often.

What this means is that 2 good days in the bond market could result in a 30yr fixed rate quote dropping by a staggering 0.75%--a relatively unheard of amount for a time frame so short.

A note on points: The much-smaller-than-normal gap in profitability between certain rates can be paid upfront in the form of "points." Using the example above, a lender makes the same amount of money giving you a rate of 5.875% with no points or 5.125% with 0.79 points.

Which is better? That's up to the borrower. It would take roughly 17 months to recoup that extra upfront cost via monthly payment savings, and rates could easily drop enough between now and then that it makes much better sense to refinance. The comparison isn't the point (no pun intended).

The point is that "points' are more prevalent and more valuable than normal--a fact that helps us reconcile seemingly big differences between lenders as well as rate quotes that might seem too low to be real at first glance. Thanks to points, there were plenty of 30yr fixed rate quotes at 4.625% by Friday afternoon this week.

Other news this week:

Many of the links below have the full story on several of the week's biggest developments, but to be sure, Thursday morning's GDP data was the biggest market mover of the week for rates. We also heard from Powell and the Fed on Wednesday and although the Fed hiked rates by 0.75% again, markets had long since priced that in.

Powell shifted the Fed out of the path of clearly telegraphed rate hike amounts. Market participants debated on whether or not this was rate-friendly, but the best takeaway is probably that the Fed will be guided by upcoming data when it comes time to decide on the size of September's rate hike. That assessment is nicely in line with the relative calm in bond markets for a Fed announcement afternoon.