After years of quantitative easing, the Federal Reserve is estimated to own $1.75 trillion in agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS). The securities are issued by Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae (the GSEs), backed by conventional mortgages they aggregate and guarantee, and Ginnie Mae, which does the same for mortgages issued with FHA and VA guarantees. The Fed has been buying agency securities since 2009, moving to keep money flowing into the troubled residential housing finance system. Even after it stopped putting new money into MBS the Fed continued to reinvest funds in the securities as old issues matured or were paid down.

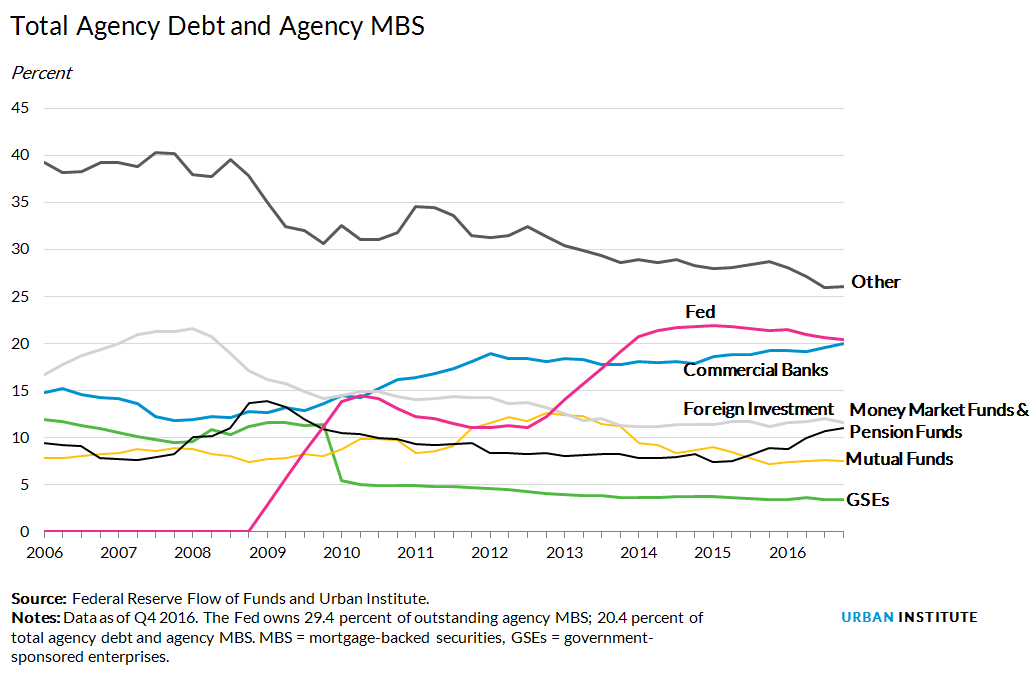

The Fed has always said it would not stop its reinvesting until interest rates began to rise. Its Open Market Committee (FOMC) has now raised the fed funds rate three times since December 2015 the markets are being to expect a change in the reinvestment strategy will be made soon. This week Laurie Goodman, Codirector of the Housing Finance Policy Center at the Urban Institute (UI) and Karan Kaul, a UI research associate questioned, in a UI blog article, what might happen when the Fed begins to unwind its portfolio which now represents nearly 30 percent of that market.

As the largest single holder of the securities, there is no question, UI says, that a Fed pullback will have important implications for the mortgage market. However, the way it goes about the change will matter almost as much.

Goodman and Kaul say the Fed has a range of options. The least disruptive strategy would be to gradually reduce reinvestment of principal pay-downs; a more aggressive step would be to cease reinvestments entirely and then let the MBS run off naturally, through prepayments. The authors point out that because of prepayments the average life of an MBA is far shorter than its maturity. The most aggressive move the Fed could make, and one they say they are not considering, would be to sell their portfolio on the open market. A recent survey by the Fed found a large majority of market participants expect the gradual phasing out will, initially at least, be the option taken.

Goodman and Kaul point out that even a slow unwinding of the portfolio over time will reduce a major source of demand for agency MBS. This will certainly put some upward pressure on mortgage rates although there will be other factors.

In addition to the path the Fed choses, the impact on the housing market will be determined by how it is implemented. For example, if the choice is a gradual phasing out of reinvestments, the pace of that phasing out will also be important as will how any option is allocated across the agencies. If the focus is on Ginnie Mae investments, there would be a greater impact on first-time homebuyers and those of low and moderate income, and veterans. Picking Fannie Mae and/or Freddie Mac securities would affect conventional loan borrowers.

These choices will be important to housing affordability, already tested by rising interest rates and home price gains that have pushed homeownership out of reach in some areas. But the UI sees the Fed wind-down raising another important policy question. "Should the agency MBS market continue to rely on the federal government for protection during turbulent times?" Before the recent financial crisis, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac's retained portfolios acted as a backstop, although at a substantial risk and cost to the taxpayer. Now the Fed has filled that void, although the GSEs bought opportunistically with a profit motive when spreads were wide, while the Fed treated its purchase of MBS as a monetary policy tool.

UI concludes that, as policymakers debate the future of housing finance, they will need to decide if there is any role for MBS market intervention in the future, and, if yes, the most appropriate structural framework for it.