Even as flood water continue to sit in living rooms and kitchens across a large swath of North Carolina it is clear that most of those homes are not insured against the damage. Mary Williams Walsh, writing in the New York Times, says that in North Carolina and South Carolina, which suffered less widespread damage, only about 335,000 homes in total have flood insurance.

The Urban Institute (UI) reports that the number of policies homeowners purchased through the National Flood Insurance Program (NIP) has declined over the last ten years and the total is now just over 5 million nationwide. There are also some private insurance policies, but nowhere near enough to cover the affected homes.

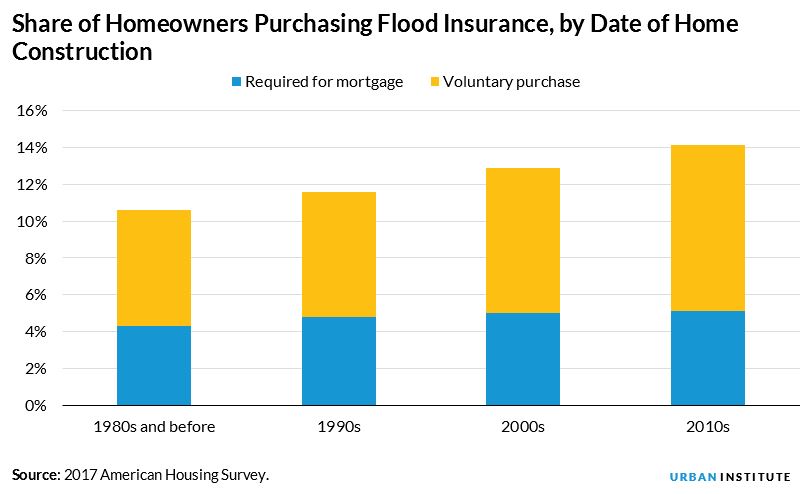

Sarah Strochak, Jun Zhu, and Laurie Goodman used data from the Census Bureau's 2017 American Housing Survey to compile their report published in UI's Urban Wire blog. That survey reveals that just over one in 10 homeowners have flood insurance nationally although in areas more prone to flooding like Miami the number increases to one in three.

The AHS asked survey respondents whether they carried insurance and if so whether it was because it was required, they bought it after a neighbor did, or some other reason. The last two answers were counted as voluntary purchases. Of all homeowners who had a flood insurance policy in 2017, 60 percent chose to buy it on their own; 40 percent were required to do so by their mortgage lender. Homeowners who live in Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) designated flood plains are required to carry insurance if their mortgages are guaranteed by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, FHA or the VA.

The UI authors say this high voluntary participation may be because mortgaged borrowers are highly conscious of the extreme damage that floods can cause or because FEMA's flood maps are outdated. It may also because homeowners without mortgages who purchase voluntarily are skewing the voluntary participation percentage.

Newer homes are more likely to be insured than older homes and also more likely to do so on a voluntary basis. Flood insurance coverage increases from about 11 percent for homes built in the 1980s with 59 percent purchased voluntarily to 14 percent and 64 percent for homes built since 2010. The authors say this trend may mean that owners of newly built homes, which are generally more expensive than existing homes, are more aware of the possibility of flooding and are looking to protect their investment.

Walsh, in her NYTimes piece says that if NIP worked as intended, more people would have coverage, but it doesn't work that way and she gives a brief recap of its history to explain why.

The program was established by Congress in 1968 in hopes of luring insurance companies back into the market they had abandoned after the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927. Flood insurance was essentially nonexistent over that 40-year time span and when floods occurred, all that victims could hope for was a federal bailout to keep families and businesses out of bankruptcy. Congress decided it would be less costly to taxpayers to identify properties likely to flood, require their owners to buy insurance, let a pool of reserves build up and pay flood claims from it.

Walsh says the program was originally a partnership between the government and about 130 insurers, but there were policy disagreements and by 1983 the companies were gone, and the government was running the program alone. Today the National Flood Insurance Program is part of FEMA.

According to some, the program doesn't work because the mandate to require insurance for homes in flood plains isn't enforced. Walsh quotes Howard Mills, a former New York State insurance superintendent, who says "There are lots of holes and gaps, and people just don't get coverage. Flood plains change as land is developed, and the government's maps become outdated. People buy houses without knowing they are on flood plains, or they pay off their mortgages and let their policies lapse. Those who inherit property may never have mortgages to begin with."

A study in 2017 recalculated flood exposure using newer techniques than those FEMA uses and found about 41 million people live in 100 year flood plains, more than three times the number enrolled in NIP. They expect this number to keep rising because of climate change and demographic trends and for the program's financial exposure to increase further because of home price gains. Congress has repeatedly cut funds for flood mapping, so it is unlikely that FEMA will update its technology.

The research report found FEMA's maps were fairly accurate in coastal areas but missed many inland risks which in some ways are more dangerous. The National Hurricane Center that hurricanes caused more than half of their deaths, from flash floods, mudslides, and drivers blundering into deep water, after they moved inland.

And it is these inland people who are least likely to have flood insurance. One estimate is that a quarter to a half of the people in the coastal Carolina's have coverage, probably because they are aware of the risks. Inland, there are places where the insurance is virtually non-existent.

And NIP itself must frequently resort to life-support. Congress lets the program lapse on a regular basis and it has been seriously underwater since Katrina, running an annual deficit averaging $1.4 billion since the storm. It currently owes Treasury more than $20 billion and that debt reflects the balance after Congress forgave another $16 billion. Taxpayers are still paying to bail people out after floods.

NIP needs more policyholders to spread risk over a larger group. One solution, especially as floods seem to be affecting increasing numbers of locations, would be to require it for all homes with federally guaranteed mortgages. Congress tried another alternative to balance the books a few years ago, taking away the federal subsidy for policyholders. Premiums shot higher, homeowners rebelled, and Congress backed down.

Preliminary estimates put loses from Florence as high as $13 billion. NIP has about $6 billion in cash on hand and a remaining $10 billion of its borrowing capacity from the Treasury. The end of this hurricane season is 48 days away. Assuming of course that Mother Nature owns a calendar.