Another in a series of articles from Corelogic Senior Product Manager, MaiClaire Bolton, about assessing earthquake risk from a mortgage and insurance perspective focuses on the Pacific Northwest. While the region is not generally high on the list, at least in the public's mind, of those that are earthquake prone, Bolton points to a massive 9.0 quake in 1700 that ruptured the full 600 mile length of the Cascadia subduction zone, a fault which runs off-shore, paralleling the west coast from Vancouver Island, Canada to Humboldt County in Northern Califonria. The quake was followed by a massive tsunami which inundated the coast and even affected Japan. That country's history records an "orphan tsunami" the source of which was for hundreds of years unknown.

For many years, scientists believed that the Cascadia subduction zone was one of the few on earth that did not produce massive earthquakes. Then when Mount St. Helen erupted violently in 1980 they realized the zone was still active. Bolton explains that, in a subduction zone, an oceanic tectonic plate that is created at an oceanic ridge pushes beneath a continental plate. "The descending plate will continue to be pulled, or subducted, under a continent until it reaches a depth at which it begins to melt. The melting of the plate at depth produces magma which then ascends through the continental plate where it is expelled by volcanoes."

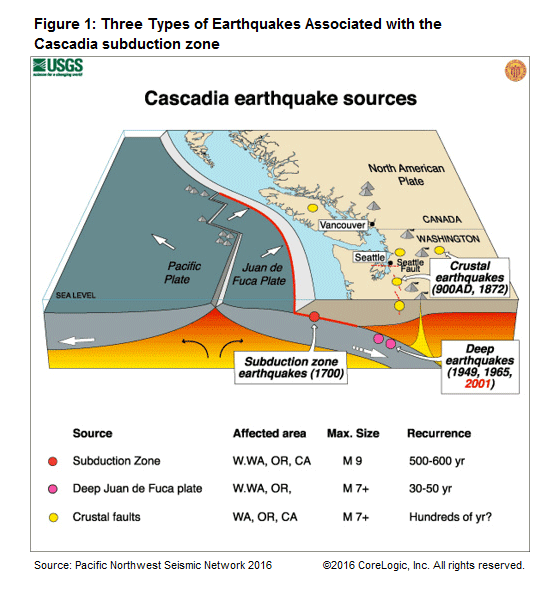

These megathrust, or giant, earthquakes are one of three types of quakes associated with the Cascadia zone. They occur, on average, every 500 years but sometimes the entire zone does not completely rupture. These partial quakes occur more frequently with a recurrence of perhaps 240 years. The other two types are shallow or crustal earthquakes - and deep, or intraslab, earthquakes. While the maximum magnitude of shallow and deep earthquakes in Cascadia is expected to only be approximately magnitude 7.5, if these events are located near an urban center like Portland or Seattle, they could be catastrophic. Deep earthquakes are usually of a lesser magnitude than crustal but are the more frequent with large magnitude events recorded every few decades.

Bolton says understanding the massive megathrust earthquakes is critical for managing earthquake risk because their impact would be disastrous. While very rare, a full rupture of the fault would be similar to the 2011 magnitude 9.0 Tohoku-oki Japan earthquake. It is also important to recognize the triple threat in the zone.

The most recent deep event was the 2001 magnitude 6.8 Nisqually earthquake south of Seattle. Given its depth of approximately 50 kilometers (30 miles), this earthquake caused relatively low levels of damage and loss. Notable crustal quakes include the 2011 earthquake in Christchurch, New Zealand, the 1989 Loma Prieta, and 1994 Northridge earthquakes in California. All resulted in considerable damage and at least some loss of life.

Among the largest crustal earthquakes in the Cascade region were a magnitude 7.3 event in a sparsely populated area of Vancouver Island, Canada in 1946 and the 1872 Lake Chelan earthquake east of Seattle which had a magnitude estimated at 6.8. Even given the limited populations, each caused considerable damage. Bolton says a similar event today, especially if located near one of the major cities such as Portland or Seattle, could be catastrophic and one of the most significant crustal faults traverses east-west through the Seattle metro area.